Pretty nice. As with Definitive Edition I again don’t see it threatening to oust my affection for Xenoblade 2 any time soon, but it was a solid journey throughout.

Where to start? I suppose the first order of business in a Monolith game will always be to marvel at its production values. I played on easy mode as I tend to do in JRPGs, but I will acknowledge that the gameplay seemed to be the least weird of any Xenoblade title thus far. That’s a real accomplishment in my books. Though not using the Ouroboros forms for Skell style traversal was a huge missed opportunity. Graphics, in terms of world design and of somehow making a game like this run on Switch, were great in a way that really only Monolith is capable of. Next for music, it’s clear that this is a follow-up to the second game. There’s a great focus placed on having variety in the battle themes and on strong motifs running throughout the soundtrack, which do so much for the emotional experience. With the setting being what it was, I had spent the entire game knowing that at some point I would be hearing either Where We Used to Be or Drifting Soul. Lo and behold, when it happened at the Cloudkeep it was as breathtaking as I’d hoped. Furthermore the Moebius battle theme never lost its impact, since I do always appreciate when Xeno returns to the godsibb choir even across series and composers (ie Zanza the Divine).

But the story is going to be where the true meat of JRPG discussion will always lie. While I find the overall storyline to be less charismatic than its contemporaries due to the setting having pulled from the blander elements of Bionis and Alrest, we also see that the plot has become more character-driven than any of the preceding entries. So perhaps that’s a natural effect of this change in direction. The emotional highs hit harder than ever before.

My heart broke for Shania, watching her driven to madness by the failures of her family, friends and the world. She was a girl with a bad lot in life who was simply mishandled by the people around her. Made to feel small through a constant stream of ‘advice’ from the self-righteous. And while she obviously moves past the point of forgiveness once she takes on the whole genocidal maniac schtick, it is a tragedy that she was allowed to reach that point at all. ‘This too is one face of humanity’, right Xenoblade? As a character representing one of the more unfair faces of humanity, of inequality and discrimination, of feeling unwelcome just for existing and being looked down upon by the normal, the strong and the successful, it’s all too real what drove her there. It’s a tragedy so viscerally emblematic of the human condition, whose emotional gut punch is that much harder due to Shania being more mundane than the scorned Archadian Praetor and his chaotic Aegis. Shania was failed by others and then by herself, from something as ordinary as Ghondor’s poor communication skills being unfortunately unable to connect with her, and Xeno has the storytelling chops to acknowledge that her rough attempt at encouragement could have such negative effects. Like it’s just…it’s just a bad situation, and that’s the extent of it. Humans didn’t manage to understand each other. But that’s also what makes it so powerful.

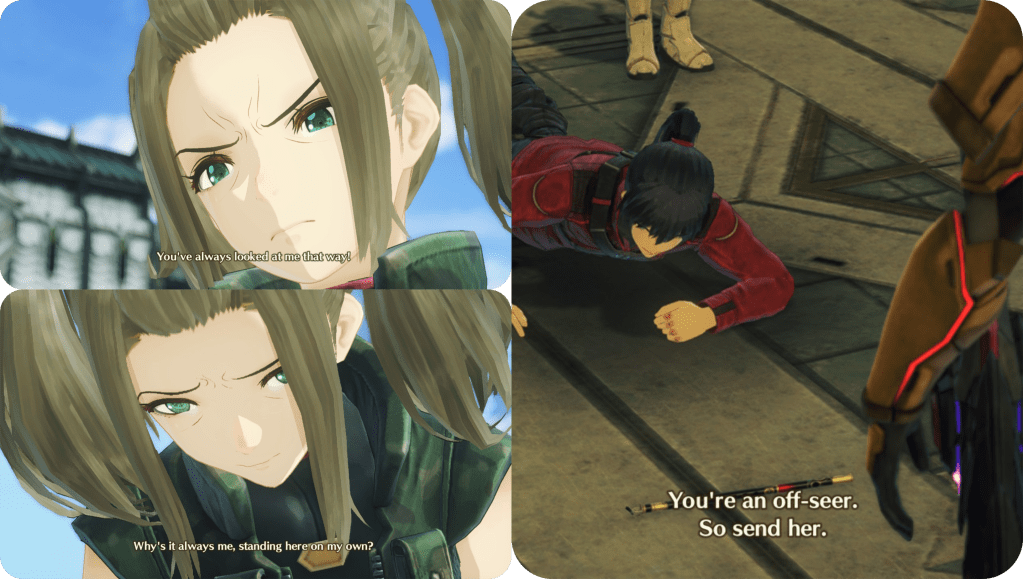

Another instance of the game kicking me down and leaving me dumbfounded would be the highly acclaimed Eclipse Homecoming scene. In the Chapter 5 finale when N kicks Noah the flute to send off Mio it made me stop to ask myself “What is the right thing to do here? To resist when they’re thoroughly defeated and potentially let their anger be the last thing she sees, or to accept their lack of power and at least be with her at the end?”, to which I was entirely unable to find an answer. The story poses some very tough questions across its conflicts, because many of them don’t actually seem to have a right answer. You get a lot more of these emotional peaks running throughout the story because unlike Xenoblade 1 and 2 it chooses to focus on the people more than the world they live in.

Characters were a real high point here. Probably Xenoblade’s best set yet, and I was made to feel that very quickly. There wasn’t any one particular character whom would come to dethrone the high points of Pyra, Jin, Lora and Malos in impact or nuance, but I have zero qualms calling this Xenoblade’s best party; Shulk’s ensemble are shockingly forgettable to me, perhaps resulting from each really only having one standout moment in the narrative. The Aegis crew are significantly better in terms of being used well across the entire length of the story and on the whole I would say that Mythra’s full storyline is still the best in Xenoblade, but the party here was so endearing. The characters have all the emotional nuance from Rex’s group worked into a bunch of less exaggerated personalities. Noah and Mio are a fantastic set of deuteragonists and watching them play out the Fei-Elly reincarnated lovers trope from Xenogears was very sweet. Sena is precious and deserves the world, Eunie is hilarious with her rough mannerisms – especially watching Taion slowly getting accustomed to them whether he wants to or not, and Lanz feels like Xenoblade finally got the big oaf archetype right after me not really jiving with its prior attempts.

But as most of the pre-release chatter would tell you, the main intrigue was the fused worlds on the cover art and the prospect of seeing fan-favourite characters interacting at a level beyond that of XB2’s DLC Blades. With regards to that, I’m unsure if it did quite enough with that possibility. On one hand – good job. It tells an honest tale of its own, refusing to let the prior stories carry the weight for it. I do respect the game for not resting on its predecessors’ laurels as any kind of crutch. But on the other, I am a fan and I wanted all the fanservice. You let me see the DLC splash screen of the three red swords together as soon as I started the game – I wanted that in the game. The mixed design elements of the two worlds don’t accomplish much beyond an occasional reference to plot-relevant events from each game’s finale. Though the Sword of the End carries its design structure and has the symbols on its Art pallette, the seeming lack of a proper Monado in play certainly felt odd and in the wake of Xenoblade 2’s revelations it did stick out to me that the only Conduit mural to be glimpsed around the world was on the Cloudkeep’s gate (though the obvious would be to assume that these are being held back for the inevitable DLC chapter). The recurring immortals Nia and Melia are sparsely present and don’t much act like their past incarnations, so the many centuries that separate this game from its prequels have allowed the mechanics of the world to shift so much that they no longer resemble what they once were. Reaching the Founders Hall and reading that Shulk and Rex may have been involved as the first generation of Ouroboros simply feels out of place.

The style is foreign to Xenoblade in a way that even the hotly-debated second game wasn’t. To me it doesn’t do enough with the fact that it’s Xenoblade 3. In fact through the reinterpreted imagery of Weltall (Ouroboros), Grahf (Consul D), Krelian (Z), Zarathustra (Origin) and the Testaments (Moebius) used throughout its cast, Xenoblade 3 can often feel more like a Xenogears 2. I was half-expecting them to play the flute section of Small Two of Pieces during the finale, even. The iterative iconography is one of my favourite parts of the franchise so I did eat up the abundant Xenogears and Xenosaga imagery that permeated throughout. It was so satisfying to see a lot of those stylistic references receive payoff by being used for actual plot parallels. Though following from this I did feel that much of my response to Moebius as villains was just going “oh that guy looks like Grahf, oh this final boss is Xenogears as heck, etc.” There are a bunch of cool fight scenes, particularly whenever Moebius D+J is let loose, but by nature of its monster-of-the-week formula the villain lineup comes up short against Torna and Zanza.

To be completely honest I do get the sense that the story cares more about Xenogears than it does Xenoblade. Since Xenoblade 2 was pulling so heavily from Xenosaga’s Zohar and KOS-MOS imagery, and its Earth flashbacks filling the role of Part I in the Perfect Works schematic, it is perhaps understandable why XB3 goes on to be so detached a sequel clearly parroting symbols and plot developments from Xenogears. However even with all that said, when you properly observe the structure of Aionios there are answers presented for a surprising amount of lingering questions from X and 2. The mysterious black knight from Xenoblade X’s cliffhanger can now be identified as a Moebius of some kind, with the dark matter that’s seen radiating off the droids in the corrupted Origin perhaps also linking the Vita/Great One back to them as well. And after always getting kickback for not agreeing with the common interpretation I feel vindicated in the confirmation that Xenoblade 1 and 2 do not end on the same continent after all, it was only Moebius haphazardly throwing them into each other for this game.

In any case. Xenoblade 3 was a great couple of weeks as I leant into it for…downright unhealthy spans of time on my days off. It was quite surprising how quickly I fell in love with the character dynamics, and I found myself constantly searching for the next Consul just to be able to hear that epic choir again. When weighed individually I find that the more shocking revelations that come from the second game’s slow-burn plot still stand as the pinnacle of the franchise for me, which easily finds its way onto my list of JRPG favourites. But when taken together the synergetic imagery sets and setting mechanics of all the Xenoblade titles (and beyond) amplify each story, turning it into much more than the sum of its parts. Takahashi has stated that this game brings Xenoblade to a close in its current form, and all I can say that it has simply been a pleasure to have received the chance to walk the worlds that this series creates.

Leave a comment