Wow. Look at this. More of the defining my terms thing that I’m doing right now and whatnot kind of maybe. The fact of the matter is that I just really like Love Live. I like saying things about Love Live, okay. This series is really, really, really damn cool and it does not get anywhere near the appreciation it deserves for its multi-threaded symbolic endeavours. I feel like the first time watching Love Live you respect its ambition, as the writers of School Idol Project visibly climb in skill along the course of the show. It’s messy, but there’s so much heart being conveyed. Like watching someone’s passion project flare to life. The second time, you come to understand the emotional intricacies of each individual’s participation in the group, and how the flip in character motivations would then make Aqours the inverse of μ’s rather than their imitation. And then like the fifth time is where you start to go “Oh, okay. Honoka did just overthrow the Abrahamic God didn’t she.” I like the cute, I like the catchy idol music. But the reason that I am so possessed by this series is because of its intensely symbolic nature. To me this really feels like the gift that keeps on giving, because the further you fall down this rabbit hole the more you’ll find the show does actually reward such exploration. The contrast between its simple surface and the iceberg of deeper meanings make it a uniquely captivating project. Serial Experiments Lain or Lum the Forever give you exactly what it says on the tin, but Love Live blindsides with the breadth of its artistry. When I produced that bigger piece on Love Live Sunshine’s assortment of imagery, I made reference to the doves as a self-explanatory indicator of divinity, but never went on to christen the biblical sub-line in a proper sequence. However this hint of Christianity repeats across the franchise, and so it’s in my field of interest to discuss it. Nico has that vision of the other girls as angels come to save her from pain, Sunshine prominently features heavenly doves and Kanon shouts her love to the school idol world with a track named Mirai Youhou Hallelujah. This franchise loves to adorn itself in church. Representation of the divine in Love Live is therefore something I’d like to reopen in order to approach it here. As fun as it would be to just drop the claim that Honoka is actually the most powerful school idol since she unironically ousts the Christian God from his throne within the original setting and then leave without elaborating, what I would think to be even more fun is to elaborate.

Thanks to her apparent powers of weather manipulation and a semi-serious timebending display in the movie, it’s a pretty common thing for fans to question whether Honoka is secretly a god. Jokingly, in most cases, but still it’s a persistent reaction. My answer to that would be to say “not quite”, on both counts. Honoka is not a god. Not any old deity, no. She is God, in a monotheistic, predominantly Christian form, and there is no joke. The film, taken with the right perspective, can honestly come to feel like a Shin Megami Tensei project in how it follows the protagonist simply wandering around the city debating both sides before making her final decision on godhood. Watching the film is mostly a straightforward experience. While the prior two cours had obvious shortcomings, it’s in this film that School Idol Project reaches the level of quality to where it feels like its properly-realised form. The production becomes complete at the same time the project does. Because of this, the symbolism that I’ve said to define the sequel so much does begin to flourish. Hidden forces begin to move. However it doesn’t reach that exact level of abundance just yet, so although there are certainly things which require unpacking in the visual terminology of School Idol Movie, the watching experience doesn’t leave you scratching your head. There aren’t many symbolic roadblocks, in fact there’s really only one particular enigma on the scene: the so-called Future Honoka. Who is this mysterious individual that Honoka keeps encountering, and why does no one else have the ability to perceive her existence? Based on her appearance and apparent access to the protagonist’s memories it doesn’t take much effort to arrive at the conclusion that she stands in for some older form of Honoka, but how? Is it symbolic or literal? Well, obviously her presence carries an innate amount of symbolic weight, or else there would be no purpose to the film framing her as such a mystery. But despite evading the perception of her group members, I would purport that she certainly is a literal being too. Or perhaps conceptual being would be more apt. Future Honoka is a real, actual presence that descends upon the protagonist. Although it may be tempting to assign her as a coping mechanism conjured up to protect Honoka while lost in New York, or to project her own insecurities about the future of the group onto, I feel that’s out of tune with the broader tale of divine acquisition that Love Live is secretly telling. Future Honoka is not a figment, but an apparition. That, simply, is God. Honoka in the holy garment. Once she’s paradoxically accepted the throne from herself and come to exist across all span of time and all place. She travels back to this origin point in order to nudge her flesh onto the path of pantheon, which is why after their first meeting the film makes such a big deal out of Honoka’s shadow forming the Christian cross symbol.

I’ve talked at length about the way in which Sunshine’s heavenly lexicon turns Love Live into a tale of deification. It’s the strangely ambitious outlier in the franchise. Yet any time I go to rewatch Love Live Sunshine, I actually feel it necessary to start off with the School Idol Movie. This seems to be the point where they conceptualised their grand narrative, and is accordingly the starting line for much the stylistic decisions in the sequel. Obviously it well predates Aqours, but I think it’s important enough to them and the show’s directing style for its own events to simultaneously be considered the beginning of the Sunshine chapter, rather than just a prequel. You cannot have Love Live Sunshine without Sunny Day Song, and you cannot have any of its imagery until Honoka becomes God in the film. It just doesn’t work that way, because the first season of Sunshine is focused on adding new depth to μ’s just as much as it does for Aqours. The next chapter adopts School Idol Project as the backbone. It is, to a large extent, a discussion between Honoka and Chika. The weary one’s conversation with God. Even before getting into any kind of biblical claim or subnarrative, that is Love Live Sunshine’s main focus. Chika spends the series having this metaphorical conversation with μ’s to help her ascertain what shape Aqours should take on. The character narrative sees Chika weighing her own leadership skills against Honoka and getting let down by the results, and more broadly it centres on her fixation on the μ’s legacy – ‘the light that can never be reached’ – the light of the divine – and how she reconciles the growing realisation that she will always come up short against Honoka. μ’s? A power unrivalled. But Aqours, well, for most the show they’re considered weak. And you don’t really appreciate how fearsome μ’s were until Sunshine makes it a big deal. So what causes the vast inequality? Through the sequel’s contrasting themes we’re told the reason for this is that μ’s, standing in for the Christian God, had something very special which she doesn’t. A flame as fierce as it is gentle. A wish extended out into the world. Love. μ’s exalted love above all else. Something so simple, yet at the same time so impossible to grasp. That is what separates Honoka from the rest. She loved more than anyone else, and she let that love become her greatest power. Whereas Chika, for most of the show, does not have much love to offer. Not for the world, and especially not for herself. She’s empty. The apathetic, self-loathing monster that she is idealises the holy, on a misconception that servitude will make her eligible for unconditional love. Her efforts over the first cour are resultingly hollow, as though she acted on the teachings but had no faith. Chika tried to bypass the struggle by simply imitating Honoka’s form, therein missing that the goddess’ actual wish was for a flourishing world of school idols and individual expression. And so God turns her face.

This may reveal an interesting perspective – something that anyone familiar with the idol section of media has surely brought up in jest before, but perhaps taking on new life in this story. That inequality, is that it? Is that what the ‘idol’ means for the symbolic language of Love Live? Within this reading it perhaps carries the religious connotation of ‘idol’. Sinful, materialistic god figures that populate an aesthetic pantheon in opposition to the true monotheistic deity. Idols are an inherently vain creature, after all. Traditionally, they represent a manufactured happiness, clothed in glorified greed. And that’s what makes μ’s unique in that world, why they alone are somehow transferred authority from the setting’s original governing power (I’ve called its imagery similar to Lain, I’ve called its divinity similar to Shin Megami Tensei, its application of Christian symbols calls to mind Evangelion, and hell, I guess here I’m calling its concept similar to Lum the Forever – Love Live is just cool dammit!). They do want to win the Love Live, but more than that they only want to spend time together while they can. To sing and dance, and generally just bask in each others’ presence. These were nine girls that became isolated by their varying social circumstances until Honoka pulled them into a friendship circle. Honoka is the one that defines μ’s, a girl with so much affection and passion to give. μ’s are the only group in the school idol scene shown to be selflessly acting for a genuine love of the people around them, and thus are the ones permitted to become God – to become eternal love. In a world of idols, a world of performative vanity, the genuine heart of μ’s lets them grab hold of the god that no one else could.

All that Christian symbolism in the School Idol Movie with Angelic Angel, Honoka’s cross-shaped shadow or the ever-present doves does actually go somewhere. Honoka is now sitting behind the scenes as a governing power. Sunshine mimics School Idol Project because Honoka is elevated to become a functional god touching the world from an unseen place, and these episodic parallels are the trial that she’s handed down to Aqours. By denoting their influence in Sunshine through doves and godrays μ’s are converted into scripture, and those in the new world then spend their days trying to interpret the Word in order to perform miracles. Love Live Sunshine is centred on miracles. There’s an abundance of Christian-centric imagery that follows through on the biblical implications woven into School Idol Movie’s subtext. For example, one of the more interesting factoids is that Uranohoshi is actually Catholic school. Glimpses of the Virgin Mary can even be seen in certain bits of promotional art.

It doesn’t play much a part in the anime, but resulting from its set history as a mission school there are a number of things done in Love Live Sunshine that go about creating a symbolic recognition of Uranohoshi as a kind of church hall, where Aqours have gathered as congregation. Dia is shown to hold her arms in prayer as she preaches to the protagonist about how μ’s are creator gods. They’re specifically called ‘the origin of life equivalent to scripture’, indicating the importance of recognising μ’s as biblical counterpart within the narrative framework. This sentiment becomes relevant again when Mari later expresses her desire to disown a monotheistic God. And at the school’s closing festival, the entire student body all come together to sing as choir. Their voices ring throughout the night, accompanied by the crackling bonfire. By the time the sun rises, only embers remain. In context, the smoldering bonfire can be seen as an image resembling the sacrificial lamb of the Old Testament. An offering burnt upon the altar as a show of allegiance, determination and plea to the watching God. Even though the Uranohoshi chapel gets taken away, the New Testament iterates the idea that a church isn’t the cathedral but the people. Anywhere there are believers gathered, then there a church stands. That doesn’t appear to be the case in the more ritualistic field of Catholicism, yet although Uranohoshi is a Catholic school itself that principle still gets reflected in Love Live Sunshine’s religious parts regardless. The girls struggle to convert an increasing amount of applicants in an attempt to earn favour with the overhanging God via their good deeds, but this isn’t how that body of faith works so they’re offered no such miracle. God sees through the mortal’s attempt to force her hand, and in consequence only 98 out of the 100 needed applicants are gathered by the time the deadline hits. However, these punishments are designed by Honoka to build their faith as school idols. To sort of tear away their materialistic shackles so that they’re faced with a crossroads, from where they can choose to begin engaging from a place of personal investment. Aqours are the sort of girls who needed their eyes cast away from the glamour before they become able to understand the message encoded into Sunny Day Song. Burning Uranohoshi upon the altar is how they gain true favour with Honoka as God, and grow powerful enough to perform a miracle wherein they fracture physical space to send feathers out into the crowd. They’re baptised through Water Blue New World, where the stage set gives them temporary access to the heavenly realms. Competing at the Love Live final is when the group well and truly comes to realise that they love being school idols and that the loss of the school and third years will not be enough to shake that faith. Aqours will continue, which is what Honoka wanted for them. To persist and proliferate. Sunny Day Song was Honoka singing for all school idols who she knew would come in her wake, and so by deciding not to quit they align with her values. The sequel film begins in the immediate aftermath of this religious growth, and chooses to signpost it by incorporating very familiar imagery of Chika walking on water, or the doves now being drawn like church art instead of the actual animal. I’ll say it again: Love Live, it adores its Christian symbols. They are all over the Sunshine saga, and even if they’re comparatively absent in Superstar that still chooses to denote its presence as a mainline entry by having its first insert song be a hallelujah. In the after-credits scene of Over the Rainbow we hear a pair of girls decide to be latest in the line of those who have adopted the continuing Aqours name. Symbolically, this is Chika’s moment triumph, where she becomes ‘right with God’, since the missing two spots are filled, and the girls become part of the Uranohoshi school idol group in spirit. Although they are separated from the building, the church continues in them.

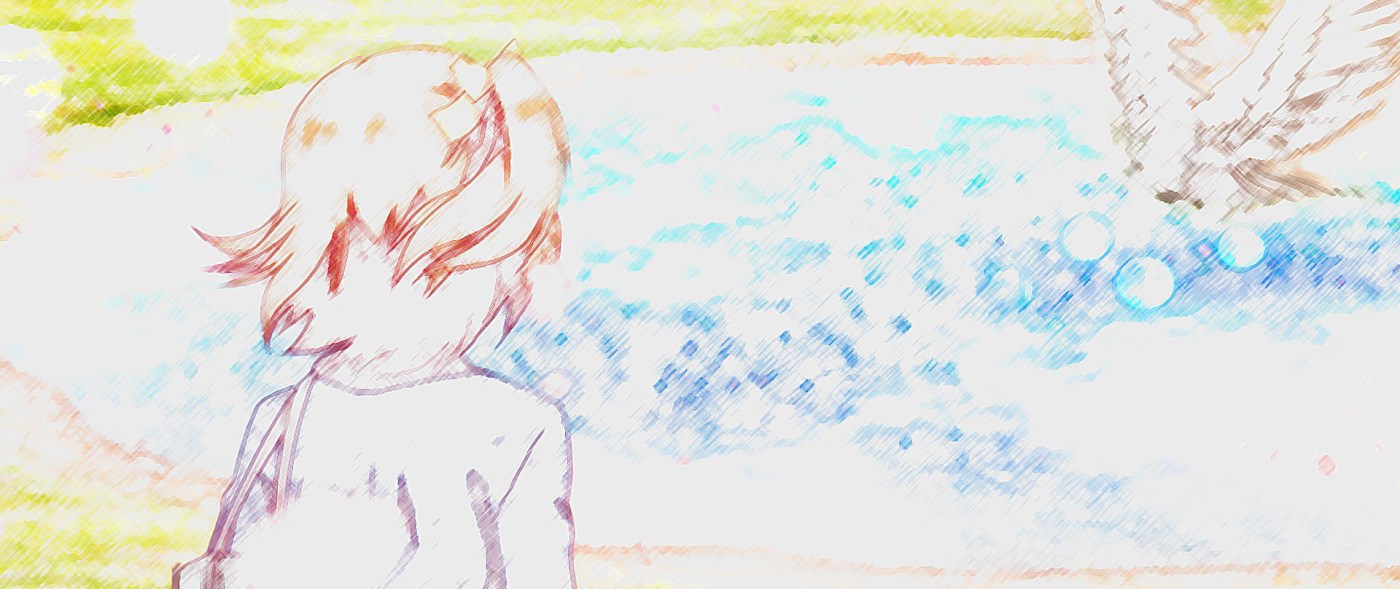

Returning to Dia’s previously raised suggestion that μ’s are now enshrined as creator gods, there is once again an obvious biblical progression at play. As Chika has said, what was special about μ’s is that they ran straight through a place that had nothing in it. They were free, and that’s why they could fly. With her choice of words here, Chika is making specific mention of the pivotal scene in School Idol Movie where Honoka takes the seat of God. In the third act of the film, where her divine half manipulates the ether and pulls her into a heavenly space. Future Honoka assures the protagonist that she can fly any time she wants, and this prompts her to begin running down the hill toward the water. She passes by the apparition, accepting its divine attributes in the process, and then flies over the pond.

In this moment she embodies the spirit upon the primordial sea that gets told of in the book of Genesis. By hovering above the deep and channelling the Creation story, it fulfills ancient prophecy and she is thus awarded her royalty. Honoka is now director and deity, which we will see is actually very integral to understanding the symbolic mechanisms of Sunshine. Her spiritual essence and character definition have been transformed. With her newfound capacity to freely redefine the setting around her, Honoka stands before her church at the venue of Sunny Day Song. She reaches to the sky, and she takes the sun within her hand. The significance of which is revealed by how heavily this perspective shot of her arm reaching forward gets repeated in Love Live Sunshine. The divine light – the sunshine – creates the theatrical world which Aqours come from, where miracle and magic become possible with enough power. We see them struggle throughout the series to wrack up enough strength, until they finally perform magic at the Love Live. That element of the setting, wherein Honoka recreates the world, is something which relates back to the firmament in the book of Genesis. In its simplest form, the ‘firmament’ in biblical lore is understood to be a sort of barrier encasing the ancient world. Prior to the Creation, all on the physical plane was water. It was deep, dark and empty. The spirit of God moved upon the water and it created the ‘firmament’ to split the sea into upper and lower portions, to create a space in which the dry land could be carved out. A gigantic, solid dome encasing the land. Nowadays that is more interpreted to be synonymous with the atmosphere, but but in times long past the ‘firmament’ was treated as though the world itself had a roof. This parable is parroted in the franchise. Inside the setting of Love Live, the firmament surrounding Honoka’s redefined world is a gigantic, metaphysical theatre hall. Now, unlike the Aqours film titled Love Live Sunshine! The School Idol Movie: Over the Rainbow, the μ’s School Idol Movie does not have a subtitle attached to it. But if you were to go and search for one in the supplementary material, you would find it in the soundtrack – Notes of School Idol Days ~Curtain Call~. Ergo, this film has the potential to be understood as Love Live! The School Idol Movie: Curtain Call. The suggestion I’m making is that the Recreation story places firmamental curtains around the world in preparation for Love Live Sunshine, and the subtitle can be used as extra context for that. It further helps to cement the theatrical image that arises in the wake of Honoka’s ascension, and can explain the decision to include a theatre intermission after Sunshine season one and the curtain call after season two. The curtains seen in Sunshine are tantamount to firmament. They’re a dual physical and spiritual phenomena one layer higher than the world which barricade everything and permit its inhabitants to have a more deliberate experience of reality. Love Live Sunshine’s cast frequently utilise excessive body language or dramatise their reaction to things, because on some level they are actors. The spotlight frequently shines upon Chika from somewhere behind the ephemeral scenes. They communicate through narration, or they do many things that can only be called rehearsed; everything that Aqours do is knowingly performative. Come the sequel, the setting is now boxed within the stage boundaries of theatre and its participants are therein frequently permitted to distort the stage set (reality) with their acting.

The theory of ‘firmament’ in a biblical context evolved over the course of early human history. Originally it was envisioned as one big dome covering the top of an earthen plain. Outside the dome still remained the infinite, dark primordial sea. At the vertical peak it was proposed one would find a number of chambers that comprised Heaven (hence how the mythological Tower of Babel was ever intended to physically reach Heaven); and true to this, where do we see μ’s in Love Live Sunshine’s first episode? Inside a distant white star that sits at the top of the world. By associating themselves with light in the final song Bokutachi wa Hitotsu no Hikari, whose chanting around the midpoint could potentially be argued to be “hallelujah, hallelujah, hallelu, hallelu” on the basis of syllables and synergy with the other biblical elements, μ’s have firmly rooted themselves as patrons of Heaven.

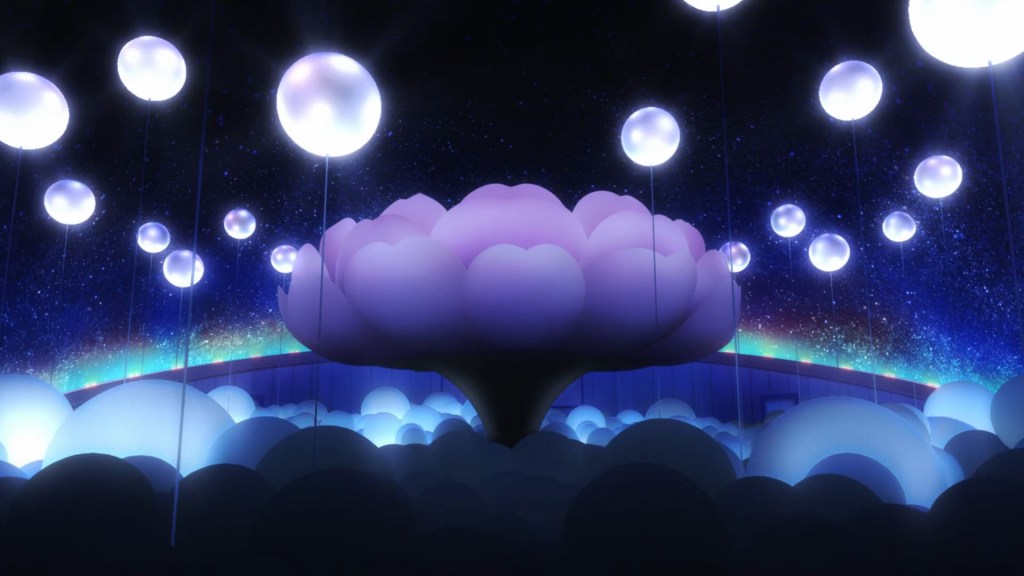

But Heaven is not presentationally limited to just them. Aqours are shown to reach that paradise as well. At the end of the story Aqours have ‘become right with God’ by inspiring the new pair to partake of their name (therein understanding Honoka’s true church – wanting fellows rather than followers), and for this the girls are awarded entry into her Heaven. In Next Sparkling the costumes are bright robes with wings. This design is the mark of their departure. Aqours are taken to to be angels in Honoka’s heavenly court. Midway into the performance they’re whisked away, traversing outside the firmamental boundary into their own eternal moment – their own divine chamber, which is once more seen to have the outer shape of a star.

So does that mean Love Live was secretly a flat-earth propaganda piece all along? Well, decidedly not, with the implementation of the celestial spheres clueing us into its preference for the Aristotelian firmament instead. Once upon a time in ancient history the world was perceived flat, yes, but philosophers of considerably more recent times would later question this design. Aristotle being the name of most import here for positing that surely God’s work must be perfect, and if the only perfect shape is a sphere then really the math speaks for itself. There’s no beauty in the planets and heaven simply being flat. This suggestion gained favour enough for the dominant framework to be modified so that the Earth and firmament must be round. In accordance with this, the prior idea that if the Earth was flat then Heaven was just ‘straight up’, sitting right beyond the sky, lost relevance. It was theorised that the globe was instead bordered by a number of celestial spheres suspended in the heavens. Each body orbited around the Earth, encased within a kind of ‘crystal sphere’. It’s at the final step outward one would now find the firmamental border, marking what we now define as the edge of the solar system. Space was what they understood to be the heavens, and then you would find outer heaven, or empyreal heaven, sitting beyond that. So what relevance does this carry for 2013’s hit anime idol series Love Live School Idol Project? I’m getting to that part. Although the depth at which it engages with it is in question, it’s already been established that Love Live is dealing in the Christian arsenal, due to undeniable adaptation of the cross and doves. I’ve then interpreted this to say that the School Idol Movie’s secret narrative is about Honoka usurping the Christian God to incite a new Creation story, and in doing so visually engaging with the classical firmament. That’s where the imagery is pointing itself. The girls dance upon the root of Creation, the Garden of Eden; saying ‘let there be light’ as they enter the chorus, and seeing nature spring to life everywhere they step. Therefore, the highlighted cosmological arrangement here, in conjunction with everything else, may hint at an inner meaning having been built into the final stage. That of the Aristotelian firmament. Bokutachi wa Hitotsu no Hikari occurs on a stage in the dark sea of stars. I would suggest that we have the grounds to interpret the surrounding assortment of glowing orbs as symbolic of the celestial spheres. This moment is the crystallisation of the group’s biblical ascendance into the empyrean, the very point at which they leave the human plane and vanish into the eternal. Their last performance as children of men. It’s an interpretive dance – a ritual – that they use to evoke their heavenly forms, at the end seen being swallowed into a blinding white light, which Sunshine informs us is a star at the edge of space. Similar to the relationship between the Lain projects, the two central Love Live series have this link between them where you’re intended to take them in tandem as they cross-reference and explain the other. At the end of Over the Rainbow we see Aqours, in no uncertain terms, stolen from the world and honoured inside their own star, which illuminates us to the fact that this is what had happened to μ’s. In the last moment of BokuHika where the screen turns white, something happens. Terrifying, brilliant and beautiful. The face of god, come to fruition. From that moment on, they are gone. All we see left of them afterward are the disciples of a growing faith, for their own flesh has been spirited away into the realm of doves and angels. I say this in total truth, not as a thought experiment or symbolic play, but rather what I would say is genuinely, the actual, hidden meaning written right there into School Idol Movie and Sunshine, which somehow always gets overlooked and Love Live then deprived its artistic accolades. It’s a phenomenal series that offers something new every time you look into it.

There’s a lot of room for discussion, and I’ve been out of the church for a long time at this point so I’m not as well-read as I could be, but in short, the religious appropriation is as such. Honoka, through a collection of symbolically-fuelled evolutions, comes to inherit the role of overseer and redefines the boundaries of reality. That is to say, Honoka, in the aftermath of Sunny Day Song, becomes God in both symbolic and a subtly literal sense. μ’s then transcend time and Honoka takes up residence within the pocket chamber of ED2, and mostly influences the world by dispatching holy doves. Through her actions in the School Idol Movie the world’s fibre is reshaped to one where the kind of intensely symbolic interactions usually exclusive to narrative-divorced sequences such as the opening and ending animations are newly allowed to bleed into and affect the main setting. μ’s is the selfless song of love that ascend the empyrean throne to create a world conductive to her followers, who spread out into the world telling a tale of miracle. Henceforth having their synergetic visual designs become the truth of the franchise and, in the evolution of their themes, fulfilling the prophecy that is contained within the title of “Love Live”.

Leave a comment