What are the options that commonly come up in the discussion of “anime as art”? Serial Experiments Lain, Monster, Ghost in the Shell, Lum the Forever, End of Evangelion, Ideon: Be Invoked, Angel’s Egg, Cowboy Bebop, etc. In the modern era we have stuff like Flip Flappers or Wonder Egg Priority, and yes I of course am going to sneakily supplement Love Live Sunshine onto this list. All imagery-heavy works that require at least some level of narrative-whispering in order to gain true headway in. The one that I quite obviously deprived of mention for the sake of singling it out, is of course, Revolutionary Girl Utena. I don’t believe in my ability to substantiate this piece without a full rewatch, because Utena is something that I ultimately don’t have a lot of thoughts about, and what I want to say about it isn’t concerned with the symbolism anyway. It’s genuinely just that I have one sentence that I liked the wording of enough for me to want to highlight it somewhere outside the annual anime posts I’ve been doing for my blog, and the rest is merely decoration so I can say that line.

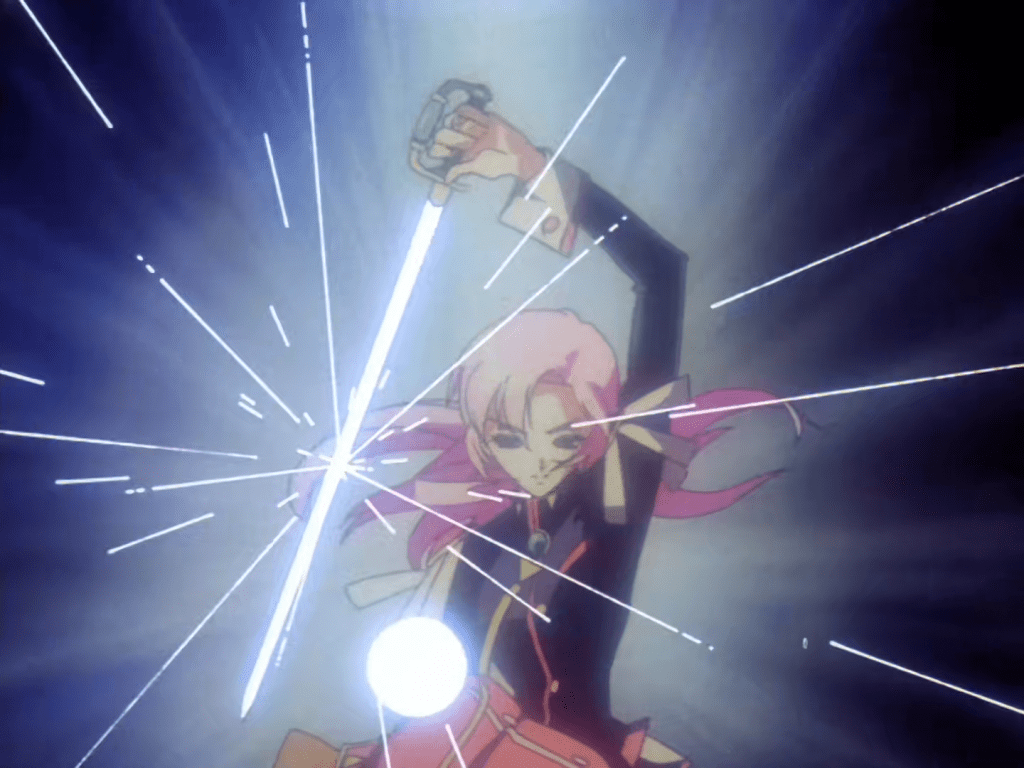

Revolutionary Girl Utena (or the television series at least) is something that I find very problematic to think upon, personally. The imagery is dense and the core experience of the show is very likely in decoding all the different symbolic meanings, but on my own watch none of that particularly resonated with me as much as the more offbeat aspects of the show did. How did my comment on it begin, again? By saying “Nanami’s Big Day Out was a fun anime, but there were too many episodes focusing on the side characters.” That’s very indicative of what I got out of it. Utena is therefore, for me, usually grouped together with Flip Flappers, and previously Lum the Forever: an abstract commentary piece that is clearly using its symbolic presence to say something, but I’m too lazy to figure out what it is. That claim does have some wiggle room since I could of course point to obvious stuff like the genital imagery when the combatants pull the sword out of their female partner, the characters climbing the metaphorical stairs of adulthood before each battle, or the cars simply being a surface-level setpiece again pointing to the next stage of life, and on the whole I do at the very least like to think of myself as someone that gets what Utena is going on about. But the specifics of each imagery line aren’t something I paid a whole lot of mind to, since there seemed to be a lot that was dependant on having knowledge of specific literature references or religious information outside of the text itself, which I wasn’t equipped to deal with.

Anyway if that poorly-placed mention hadn’t revealed it already, this is a story about adolescence. Coming-of-age told through an ambiguous moral lens, as the characters fumble around and explore various facets of themselves to feel out the kind of adult they want to become. Ikuhara uses this framing with the intention of tackling various taboos surrounding adolescent sexuality, and, given that this is in the shoujo genre, particularly that told from a female perspective. If you were to push this whole discussion from your mind then undoubtedly the first thing you would notice is that Revolutionary Girl Utena is a weirdly horny show. Everyone’s flirting to the point it thrreatens to impede the narrative’s pacing, and it seems like they all can – and do – sleep with literally anyone they can get their hands on. From an analytical perspective I think that’s really what makes it so interesting. In a sex-heavy setting which in most other cases with anime would tend to be be about the harem playboy’s erotic conquests or voyeuristic exploits, it takes, or indeed empowers the female perspective. Instead of denying it as a factor or opting to later use it for any kind of moral comeuppance, it acknowledges the promiscuity as a backdrop, works within it, and then continues on to show the girls as not having become slighted or less valid by it. The entire show is about headstrong females who aren’t afraid to engage with their sexual sides for whatever reason they see fit, – pleasure, comfort, revenge, manipulation or the like – and Ikuhara explores this to say that they are not ‘dirty’ for having been open in this way. I mean like yeah maybe they are bad people, but that’s the result of their personalities and not affixed to their sexual willingness. The two men who I suppose fill the role of main antagonists, Touga and Akio, are sleazy and that’s something which the narrative never really punishes them for. It’s just a fact of the setting that those two are constantly left to their own pursuits. Instead of Utena being the stereotypical gay anime girl that scorns all that which is male affection, she instead treads the lesser-highlighted bisexual route and the narrative thus permits her an organic femininity when she experiences an innocent love through Akio, while unaware of how deep his rot runs. Neither defiled nor defined – that sentiment is what underpins the thematic discussion present in every interaction, and from that angle it’s quite fascinating honestly. Observing the ways in which Revolutionary Girl Utena uses sexual commentary as a vehicle for psychological summaries of each character really makes it stand out compared to similar outings in the field which often begin to head down that route but then fail to commit to it and the half-realised remnants of something more ambitious then unfortunately end up as an insulting example of fanservice.

Heaven’s Feel is probably my most obvious comparison point, since that could have been an interesting commentary piece on the sexual storytelling between Shirou and Sakura regarding each party’s urge to constrain the other. It discusses nearly the exact same topic that I saw within the Utena film. The story has the setup to where it wants to be critiquing the very idea of whether love is actually something pure or not, and in a lot of ways saying that it isn’t. Their fragile intimacy, an unstable balance between trust and dependency, and overall just an urge to overwhelm the other’s freedom and claim ownership between the two of them. That really forms the undercurrent of their entire romantic and moral friction. Yet despite the chatter about the sex scenes being the film’s most vocal discourse going into it, that really only become relevant in a rare few scenes, and it sadly doesn’t do quite enough to differentiate itself from the rest of Nasu’s dumb fetish magic that plagues Fate/Stay Night. It pretends like it’s going to say something meaningful which just makes the missed opportunity that much more of a shame, though I suppose that’s simply the calling card of that era of the Fate franchise.

On its own and in view of its peers, the fluency with which Utena engages with these raw topics and turns them into artistic exploration is something to be respected. But nevertheless at the end of the day it’s something to which my main remembrance is about what a problematic spot it occupies. I like what it does, why it does these things and how it does them…but that doesn’t mean I enjoy it. Outside of the comedy moments I find that Utena can be hard to actually watch. The story’s narrative peak that all the thematic and character development leads up to is this moment near the end where Utena sleeps with Akio. For the entire second act she’s been growing increasingly smitten with him, totally unaware of the how far-reaching his promiscuity is by leveraging his power advantage over the female students, and the repeated rapes of his younger sister who happens to be her very best friend. Utena is lured in by his sweet-talking and has this uncomfortably intimate moment together with the main villain. We in the audience are screaming at her because we have all the context, but Utena is simply a girl in love.

This scene here is Revolutionary Girl Utena. All the various character conflicts contained within this single moment are what it’s all about. Once Utena does eventually learn of all his sins she doesn’t begin to hate herself or feel that she’s lost any worth. She simply hates him and doesn’t let her flawed adventures tie her down, instead accepting them as a fleeting mistake of youth. It’s narratively brilliant and implemented as a stroke of artistic genius – but that doesn’t mean that I have to enjoy it. Because regardless of whatever message Ikuhara was trying to send through all this and how it hinged on them being at the age of puberty, I do still think he should have compromised and aged the cast up. Utena herself is the same age as a Precure protagonist and that plainly just makes me unhappy to think about.

I don’t really have a whole lot to say about Utena from a character or theme analysis standpoint, I’m only here saying this because I thought the “neither defiled, nor defined” tagline was too cool to be buried within my blog. If I had to say whether I like Revolutionary Girl Utena…I’m just not so sure. I respect it a lot, but at the same time I also don’t. I did like the aesthetic and, by and large, the characters, but I can’t help it that what comes to mind first whenever I think of Utena is just how much I hated Akio. I get that it’s ‘the point’ and that Mr Ikuhara-sensei says I’m a bad person for feeling disgusted by it or whatever, but at the end of the day I just really do not like Touga or Akio and the prominent focus on their sleeping around. It is an incredible story that says some very important things, but still not my kind of story. And again, I understand that tackling that taboo is seemingly what the director aimed to do, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s not for me. It intends to make you uncomfortable, and, well, uncomfortable I am. Because I actually don’t have anything interesting to say about Utena I guess that makes this a review instead of anything else, so, uh, 7/10. Wow. Incredible. I kind of wish I liked it more given its legacy, but yeah.

Now, all of that was written under the pretense that it’d be done and dusted before I finally got around to the movie, considering I had been putting Adolescence of Utena off for two years by now. But I went ahead and watched it anyway. To be completely honest with you, based on what I’ve glimpsed of his other offerings I didn’t think that Ikuhara had it in him. Not that his other shows aren’t great, but Utena is quite easily his signature work, yet it didn’t sell me on the idea that he deserved to be placed in the realm of the abstract-anime greats like Hideaki Anno or Satoshi Kon. But lo and behold, there it is! What a film!

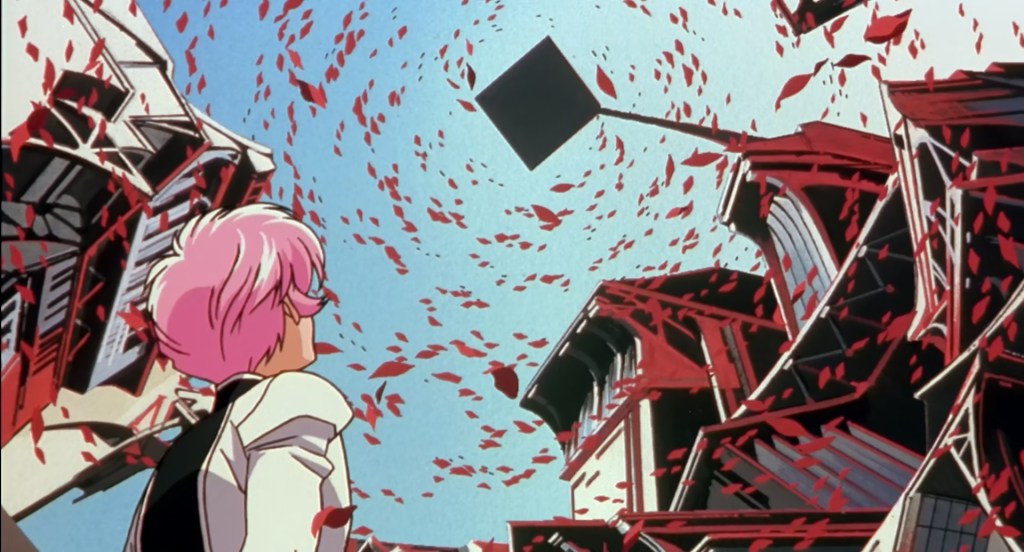

I won’t say it’s the best one quality-wise since there are a lot of anime in this artsy niche which I consider masterpieces, but even among its peers this might be the single densest symbolic piece I’ve encountered. The artistic flair in this film is outstanding. Movies are always where anime tends to truly get experimental, and when you serve that up with a heaping helping of Ikuhara’s directing it inevitably leads to a masterclass of abstract presentation. Although I do admit that my reaction during 90% of the film was “I have no clue what on Earth is happening here”, that was accompanied by a sense of awe, speechlessness, pure fascination. There I was with my big ol’ bowl of 1am potato chips ready to settle in and watch the movie, but I didn’t end up eating any of them because I just couldn’t tear myself away from the screen. The degree of artistry in this film is overwhelming – suffocating, even. Yet in spite of that I did come out the other side feeling that the tighter narrative tells its piece in a far more understandable form than the TV equivalent. The story doesn’t have time to become as expansive and multi-layered as the 39 episode series, but I think that is ultimately to its benefit.

The message, or what I could glean of it, seemed to be a different application of the stuff I mentioned before. Everyone is held captive by this fairyland castle that gives them dreams of a flawless romance, but by the end are able to take solace that ‘the prince’ has been killed. Utena having the goal of becoming a prince despite being a girl is one of the common discussion points regarding the series, but the way it’s written in the film here makes me think that ‘the prince’ is not actually anything to do with gender politics. The students are held captive by the magic castle of youth, but they eventually step into the driver’s seat and gain the freedom of the outside. At the same time, the illusion fades. They’re thrust out of the system and into a world where they have to carve their own path forward. Likewise, relationship dynamics naturally change with age. ‘The prince’ thus seems to represent the idealistic love, or the suggestion of purity in love. Destiny, the red string of fate and all that. Which, doesn’t really exist. Prince Charming is a child’s dream lost to the coming of age. Touga is Utena’s prince until he tragically perishes, and then despite wanting to cling to his memory Utena is left frustrated with the fact that she can’t stop herself from becoming attracted to Anthy. The truth of the matter is that no one actually has a soulmate. There are a lot of people one could become happy by being with, and this causes Utena a great deal of distress since it challenges her childish views. Anthy is a girl with very damaged perceptions of what constitutes a healthy relationship, and because she fell under his touch so young she sees Akio as her prince up until Utena inspires the courage to confront his sexual abuse. They become collaborators in the death of the prince, the first love’s shattering, and reach adolescence. It’s a bittersweet but ultimately necessary resolution where they depart the fantasy and begin to face the adult world in earnest.

I remember once chatting with a girl who was a huge Utena fan and she made this comparison point between it and Go Princess Precure, saying that if Utena is a deconstruction which tells girls that they can be princes too, then GoPri is a reconstruction that offers a counter-stance that it’s okay to be a princess. And while that is certainly a valid reading given that it comes from personal engagement with a multi-layered thematic journey, I wouldn’t agree with that for my own reading, since to me that’s neither how the plot progresses nor what Revolutionary Girl Utena’s ‘prince’ actually stands for. Utena does not become the prince, and the early part where she’s chasing that ideal is treated as the folly of youth. When I say “folly” I don’t mean from a gender or sexual orientation perspective where Utena is a lesbian who becomes “fixed” by falling in love with a man or anything disgustingly offensive like that, but in the sense that the prince she was pretending to be never existed. She chases its shadow for a bit before the reawakening of love forces her to look upon her heart once more. The end of her character arc sees her instead killing ‘the prince’ that was within her, realising that it’s okay to fall in love multiple times, and that innocence in such a way does not define her worth.

In review, this appears to be a far more important way to utilise this story beat. I don’t claim to remember the original with enough detail in order to comment on its usage of the ‘prince’ concept, but in the movie at least I do believe they are having it embody first love. Utena is certainly a pretty major gay icon in the anime scene and I’m not trying to undermine that, but used in this way I suggest of the film it stops her sexuality from being a mere selling point. If we were to take the other path and let the ‘prince’ refer to a discussion about gender identity and sexual orientation then it makes Revolutionary Girl Utena into an, arguably, more stereotypical story that doesn’t actually challenge archaic beliefs as much as its legacy would have you believe. It’d be a comparatively simple story of self-discovery where a previously straight girl comes to understand that she is actually gay, and perhaps to some degree on the non-binary or trans spectrum. She rejects her old lover to become the prince herself and ends the series in the arms of her own princess. I can definitely see how the ending sequence would lead one toward that conclusion. But to me this threatens the story’s artistic integrity, since it makes it all into a spectacle. Rather I believe that what makes Utena interesting is that her bisexuality isn’t a simple plot setpiece. The story never hesitates upon the matter of her being attracted to her own gender, rather it’s about her feeling guilty for falling in love a second time. And like I say, “the prince” seems to refer to Prince Charming or “first love” in my reading. Utena’s sexuality is therefore not related to the conflict at all, and simply an organic part of her character setting. Utena isn’t gay for the sake for the story, she’s just gay because she is. Which is something that I think carries a hell of a lot more meaning.

The two enigmatic catchphrases “if a chick cannot break the shell of the world it will die without being born” from the main series, and “a car without its key cannot move and goes to rust” from the film are perhaps both pointing toward this same idea. The baby bird emerging from its shell or the teenager who first obtains his driver’s license, each signify the first step into a new stage of life. If Utena and Anthy continue to reject the outside world by taking refuge in the cage that is “first love”, then they will stagnate and never truly become adults. They’re allowed to be lifeless dolls within the school’s boundaries, but to become human they have to leave. I guess that’s what Utena sets out to say as a shoujo series. They will never see the world for what it is if they keep running away from change. Thus the Utena car transforms into an exceedingly phallic shape and plunges into the depths of the undulating hallway before it, racing through to the adult life that awaits them on the other side.

This fragmented chunk of the story isn’t necessarily as ambitious as that which was mentioned above, since it occupies a much smaller slice. But this means far less plot pollution in its vast ensemble. I probably can’t say that it’s easy given the kind of confusing presentation it uses, but it is easier to take in the various character messages because the storytelling is in a more fluent format, and for every story beat from the original that gets cut out, there are multiple complex imagery lines set to supplement it. One step back, two steps forward, effectively. Or three steps, rather, since I put this at a 10. That’s how I feel about this. The original? Not really my cup of tea. But Adolescence of Utena? I feel like I finally get it. I look at this and I get why people clamour for and worship this story the way they do. I didn’t even have anything significant to say for either of these, yet here I am speaking on it anyway because it simply didn’t feel right to not channel these feelings somewhere. I am awe-struck, and becoming increasingly enamoured the more times I hit replay on the film arrangement of Rinbu Revolution. It’s damn good anime.

Leave a comment