Note: This video was prompted at a friend’s suggestion that it’d be fun for our group to make powerpoint presentations to show-and-tell our way through some things we’re especially passionate toward, such as anime, manga or games. So the latter two subjects may potentially happen at some time too. Knowing how my own brain works, and how my ability to speak coherently on command does not, I’ve thought this group activity a rare opportunity to, even summarily, produce a reflective piece in a category that I ordinarily wouldn’t. Rather ironic timing considering two of the three drafts I’m toying with at the moment currently have sections about how I would never publish a favourite anime list on Youtube due to it being a bit too personal for me who has never wanted to be any kind of ‘personality’, but in some ways very much a blessing. I’ve had a draft titled “MAL Masterpieces” stagnant on my WordPress since not teveryooo long after my first ever video essay six years ago, and at this point my writing has changed so much that I was never going to go back to it without some serious convincing. There exist a handful of pieces I’ve produced that serve as milestones for my ability to articulate my thoughts. Understanding Cloud Strife was the first time I established my essay format when my previous things had quite literally been narrated reddit comments. Explaining Iwakura Lain was conceiveod at a point where I still considered 2000 words a challenge and dared not even dream of anything in the realm of the 7000 it ended up being. And then now in my current string of projects I’ve been really reevaluating the amount of life, voice and linguistic freedom I’m willing to allow myself. Resolving to somewhat relax my previously strict definition of “video essay” (that is, a normal essay which just so happens to have voice and image attached to it, even when such a form is absolute torture to speak) to also encompass looser things like the Anime Homage in Xenoblade video, which others would probably still classify as video essays but to which I would sooner call mere “talking pieces”. This new phase being instigated through an as-of-yet unreleased Serial Experiments Lain reflective pseudo-podcast script I wrote 95% of seven months ago, but have lost the motivation to finish since I have absolutely no hope of remembering what tangents or mental connections I was making for the series at the time of writing. That script is twice as long as the previous milestone at around 15,000 words and signified the first time that degree of long-form content was ever within my grasp. But this was done at the deliberate expense of cohesion. Within the first finalized versions of every script I make there’s always a ton of rambling in it that usually gets entirely cut out, and this, uh, Rambling Experiments Lain idea was conceptualized to be one where I, for the first and no-longer-only time, stopped being afraid of leaving it in. It’s only in Of Gods and Monsters, which has released a long time before Rambling Experiments Lain ever will despite being started long after it, that I was able to then take that long-form experience and return at least some of my usual formality back into it. I’d like that to be my new gold standard, but the truth of the matter is that I poured everything I had into that. I know the end product might delude one into thinking I’m something of a skilled speaker – and personally I’m just as surprised. The actual behind-the-scenes situation is that I am a bumbling fool who takes at least twice as long to record as the final product’s runtime, because I fumble on every possible line. I swear I recorded like 10 hours of total narration for the 1 hour 40 Love Live Sunshine video. But anyway the point I was making was that each time after successfully blowing past those perceived limits it ends up making the level of language I used prior rather irreconcilable. Especially so when a great deal of the descriptions in that Masterpieces project are actually relics from 2015 themselves and read like little more than a first-year university toddler’s aimless adjective babble, though I am admittedly quite guilty of spamming adjectives nowadays still. This was a great excuse to breach the topic anew, and even in the hypothetical situation where I didn’t have any intention of publishing it afterward I still felt rather adamantly that In order for me to truly say what I like about what I like, I most certainly need an actual script in front of me. I’m just not geared for a conversational format.

My intention is to start at the bottom and work my way to the top, honing in on the specific few traits endemic to each entry that are responsible for elevating them so high beyond their contemporaries. But in the interest of any manufactured suspense and whatnot, I ought to get the obvious and obligatory out of the way first. Gurren Lagann. Both because building up to something that has publicly been my favourite for such a long time isn’t very interesting for me or you, and because there are some additional caveats to its presence on my list that make it necessitate separate mention. I’d rather do that early than chuck it in as a meandering footnote.

Similar to another entry further down, Gurren Lagann is something that I feel perhaps doesn’t get merit in places it deserves, since for as much as its common pitch is “hype robots and dumb fun”, it’s a surprisingly competent discussion piece. Even amidst its incredible animation, creative colour composition and outrageous action, the phenomenal character writing and associated thematic exploration is what really establishes it, in my mind, as the perfect coming of age story. Things seem so black and white when Simon is a kid in the first half, but once he grows up he begins to see that life really isn’t that simple after all. There are no heroes and no villains, just a cosmos of individuals each with equally valid yet totally incompatible political ideologies, and every element of the production feeds into this sentiment. Gurren Lagann is deceptively coherent in a way that a lot of anime writing, frankly, is not. Gurren Lagann is loud, but is all about the quiet moments. Its plot is larger than life yet the core experience is in the small interactions. The caveat mentioned, however, is that Gurren Lagann is my inactive favourite. It’s really, really darn good – but for whatever reason lacks staying power. The only time it ever crosses my mind is when I’m actively rewatching it. As soon as the show ends it seems to immediately leave me, and when I stumble upon a screenshot or character design there is a feeling of estrangement, like “oh yeah, that is Kamina isn’t it”. Despite being my most rewatched anime it still feels foreign to me in many ways. Every other favourite I have a dialogue with at some level of the subconscious, but TTGL is usually a void. Hence why I initially saw the need to keep more than a simple top 10. After a few years I begin to doubt whether it really deserves to remain there, and in some ways I honestly wish it wouldn’t since Gurren Lagann, not to diminish its inordinate positive qualities or anything, is nevertheless such a generic and uninteresting answer for a #1 pick. I would like my 250-days-watched 1200-shows-completed self to have a far more obscure ultimate than simply the second anime that I found when I started to get back into it again in 2011. But then I watch it again and it always ends up far better than I even remembered it. Gurren Lagann is unbelievable. That feeling fades almost immediately and I’m left with a more static definition that the last time I watched it I once again marked it my favourite anime, which I maintain as a fact-of-matter relationship until my next rewatch springs up and I am inevitably – and temporarily – enamoured anew.

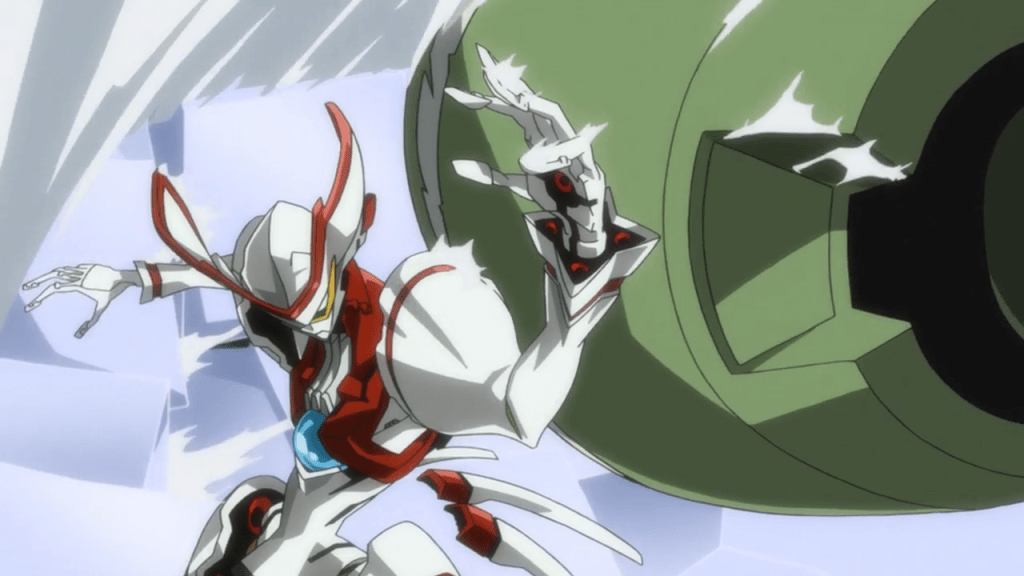

Now with that established, we head to the bottom of the list for my top anime. With Gurren Lagann out of the way there are 11 left. On a quick reflection I could, and probably would, place Star Driver as number 12 for its genius genre interplay wherein it tells a stereotypical magical girl story utilizing mechs as the mystic cloth, and for the fact that the last three minutes of the show where these two sides simultaneously come to fruition are quite frankly the coolest three minutes one will ever see in anime.

Cutey Honey crawled so Utena could walk. Utena walked so Star Driver could fly. But that’s something I’ve not yet given the appropriate amount of consideration since, as always, I’ve still been too lazy to work on the script that’s been sitting neglected in my draft section for close to three years now. I settled on a top 12, gave an acknowledging nod to Star Driver, and then effectively dropped the issue.

Finding itself worming its way onto my favourites list against all odds is Symphogear XV.

And this is something that I truly do mean against all odds for, because prior to this I had some rather choice words for Symphogear as a franchise. Words such as “what”, “why” and “how”. Symphogear, in my mind, should be the perfect anime. A lengthy anime-original with a focus on fast-paced fisticuffs and an excessive amount of insert songs, combining the magical girl, mecha and idol genres within a generally hammy aesthetic and a great many super robot references. Tell me that ain’t one of the most attractive pitches ever heard. But unfortunately it seemed like they would systematically sabotage the potential in that design at every juncture, always diluting its own quality with writing that was just too distractingly dumb to avert your eyes to. Symphogear to this point was not “dumb fun” but rather “fun and very, very dumb”. They had this innate brilliance but then went on to heap bad decision after bad decision upon it. Nothing in the show is ever foreshadowed, but rather things are simply pulled forward and reintroduced on a whim. Characters will lose arms one second only to be miraculously healed the next, death is rarely permanent even if it feels like a metaphorical slap to the face, and the Swan Song that’s supposed to exceed their limits in exchange for their lives only ever has actual repercussions once at the very beginning of the series, for the character who had to be discarded in order to squeeze Hibiki into the lineup. It’s not like I’m one to fetishize character death or anything but man, if you wanted a cheap powerup for cheap dramatic tension you could have just as easily done that by not including that tidbit about its mortality rate, because the only thing accomplished by including it is to tick me off at how quickly Symphogear forgets its own rules. There was literally no point to Kanade’s death. It’s so short-sighted and convoluted, like Metal Gear without any of the charm. Moronic above all else.

Then XV releases and it’s almost like they had a board meeting that basically just went “hey guys, what if this time we don’t do that thing we always do.” I’m talking from the perspective of giving the previous season’s finale a 1/10. But then XV’s first episode immediately taps into the perfection inherent to its design and then somehow manages to never dip. I took about a seven month break between the end of AXZ and XV, and for that span of time most of my engagment with the series was spent in lamentation or insult. I tried so hard to love it but Symphogear had betrayed me again and again. But I added XV to my favourites list literally like two seconds after finishing it. It’s difficult to pinpoint what even changed this time around since it’s still largely the same show, but XV just works in a way that it never has before. I would choose not to use the “Symphogear except good” suggestion because it’s something that I believe should be a masterpiece by right. Rather it’s more that this is Symphogear except not bogged down by any of its rampant bad parts. The idiocy is at just the right level to successfully become endearing and the convoluted jargon actually feels like it benefits the show’s voice. Watching the four seasons prior I never thought I’d be allowed to advocate for Symphogear like this, but XV is just that good I guess. This is the show that Symphogear had been trying and failing miserably to become the entire decade, and the show it rightly deserves to be.

Rolling Girls is an aesthetic overload taken in a totally different direction from Studio Wit’s usual titanic grittiness. The background art often places the characters within alluring dreamscapes using its painted style, while the foreground art has an abundance of high quality effect sakuga, and the soundtrack itself feels alive. But I think it’s really the mechanics of its narrative structure that tie the whole thing together. The show is episodic but does so through two episode mini-arcs which are framed by its road trip setting, giving each plot appropriate breathing room while allowing the girls to organically weave between all the various pitstops on their journey. It’s very pleasant.

Hyouka is all about the extravagant mundane. Extraordinary and extra ordinary all in the same instant. By the end of the series Oreki has, realistically, barely grown at all. Far from a total reversal of his character, he’s only gone through some very small developments, to the point you could sum up his entire story with a single sentence. Yet at the same time it’s precisely how regular those changes are that make them so special. Oreki is a normal guy doing normal things in a normal setting, and the narrative is written with such finesse and emotional awareness that this is exactly what makes it so strikingly unique.

Concrete Revolutio is something that perfectly hit a lot of my tastes, or perhaps even served as the specific instance which codified them. “Why don’t other people see the genius in this like I do?” was much of my internal dialogue during its airing. It’s not for everyone, but it most certainly is for me. Confusing presentation, complex meanings and colourful personalities. The nonlinear narrative and constant mental engagement required in order to decode what on earth is happening in the character politics at any given point in its disorienting timeline make it exactly the kind of confusing anime that I apparently have a penchant for, and as with all things the fantastic soundtrack helps cement it in my mind. I’ve seen many a nonlinear anime but none has done it even close to as well as this one has.

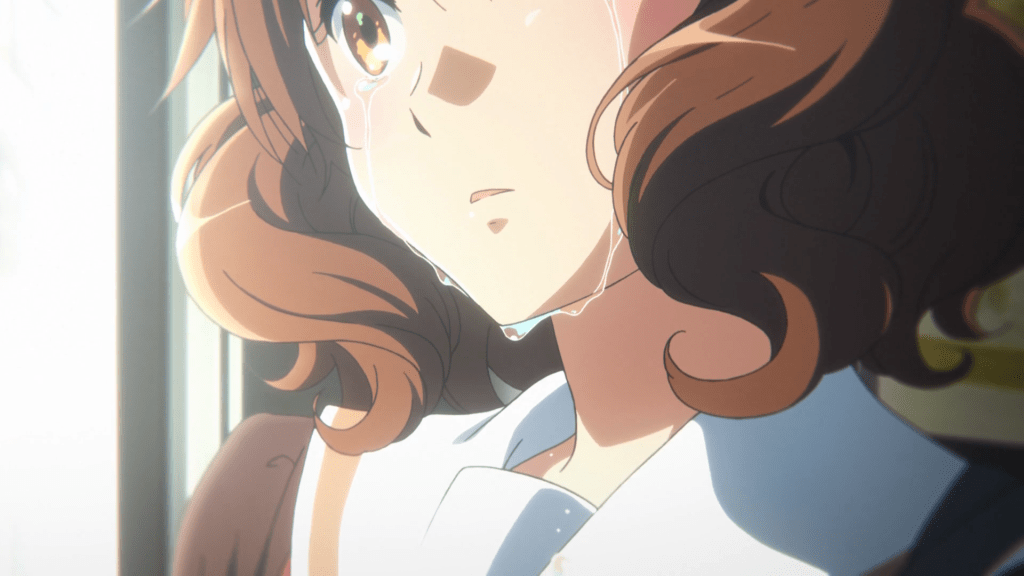

Hibike! Euphonium is something that, all things considered, doesn’t need very much preamble. It’s just good. Kumiko is probably the best character in anime in terms of visual and emotional design, vocal performance and the organic depth to which she’s written, and the show’s shot composition is drop-dead gorgeous.

Part of me does feel some level of vain hesitancy in having three separate Kyoto Animation entries on this list for how basic an opinion it is, but I suppose it’s not my fault they’re just really darn good at what they do. I can never truly decide whether this and the previous position should be switched, but generally I maintain Tamako Love Story as their peak.

The film is short enough and the pacing tight enough that there’s never a bad time to rewatch it. The cinematography is not as loud and artistic as that of Hibike Euphonium, but it certainly will not lose out. Alongside the obvious of great shot arrangement, it plays with colour depth and lighting in such a way that it establishes this very pleasing quasi-retro aesthetic. But all things considered I suppose the most memorable and impressive part of Tamako Love Story still has to be the ending sequence where the production’s strongest subplot is finally crystallized. The prequel season Tamako Market’s structure is one where each episode of the show is meant to take place in a different month of the year. Alongside just generally permitting the story to cover a lot more ground this way, it does this in order to allow long-running character growth or plot elements across a short period of time. The most significant being the, not just nonverbal, but musical narrative of Koi no Uta. It’s a small detail that pays off in big ways. For most of the early show Tamako can be heard humming a certain tune in candid scenes and though she wonders what it is she has no clue where she’s heard it before. Eventually it comes out that it’s the melody from the love song her father composed for her mum back when they were young themselves, much to his embarrassment. From this point on her usual humming is replaced with offhand scenes of her singing the lyrics, which then fully transforms into her own cover of the song when she wants to confess to Mochizou at the end of the film. I think this song, what it does as a storytelling vehicle to give direction and meaning to the show’s slice of life events, what it represents from a structural standpoint to frame the monthly narrative, is that which embodies what makes Tamako Love Story so brilliant an undertaking, and echoes its truest essence.

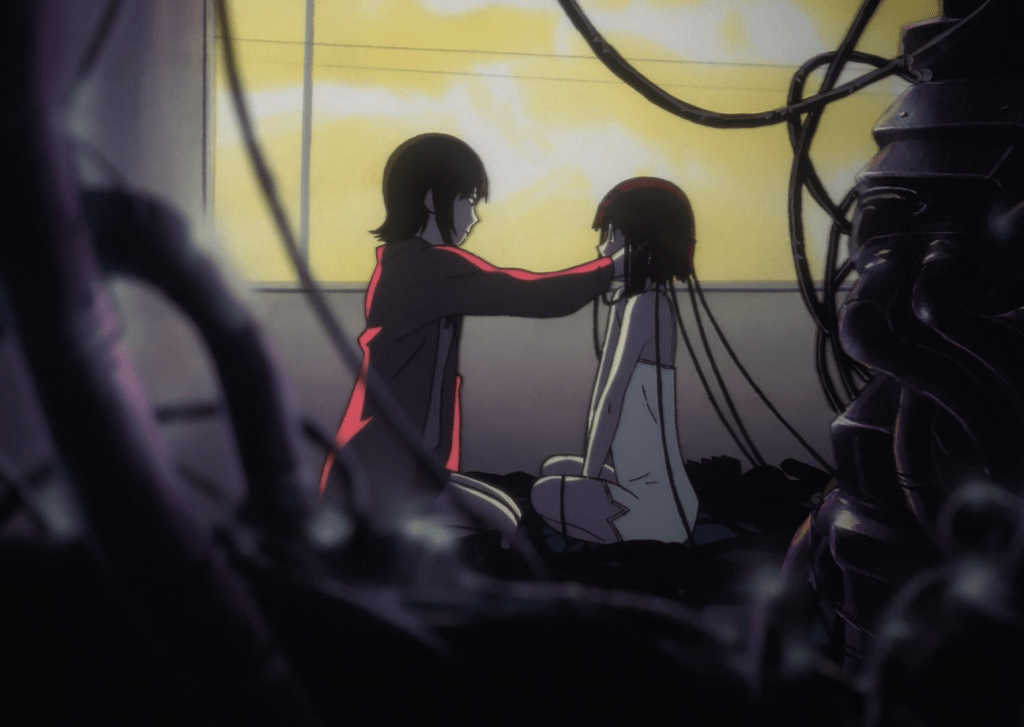

Speaking of ambiguous storytelling and confusing visual language tied together through outstanding writing, and igorning the fact that this segue doesn’t work since that was actually three paragraphs ago, it’s therefore common sense that Serial Experiments Lain has to be a mainstay of my favourites list.

The active engagement required in all layers of its theorycrafting is endless amounts of fun. There are so many different moving parts that need to slot together in order to establish a pathway of any kind that even just completing the show is a mental exercise in and of itself. I could probably rant about Lain forever since there’s nothing else quite like it. The characters exist in a strange void of abject ambiences and uncomfortably loud buzzing. It’s nigh impossible to find a foothold since the directing is deliberately attempting to attack the viewer’s ability to understand through frequent visual hallucinations and fever dreams. It’s disorienting and abrasive, using horror conventions to great effect in decorating its sci-fi stylings. Yet obscured somewhere behind all the conspiratorial actors and reality loss is a tale not of evil, not one of terrorizing its audience, but of simple love and connection. The enigmatic and ill-defined existence that is “Lain” is caught up in this malicious whirlwind of lies by the corrupt actors who want nothing more than to gouge out her very soul. Deus, the Knights, Protocol 7, the KID System, the Schumann Frequency, Tachibana Labs, the Wired, the Human Genome Project, ego death, Psyche Processors, Navis, non-volatile memory chips and the pursuit of perceptual deification – to be honest, Lain doesn’t care for any of it all that much. She’s thrust into its midst and dragged to wits end, when really all she wants is the simple allowance to persist as Iwakura Lain. The daughter of Yasuo, younger sister of Mika and best friend of Alice. Lain carries within her the power to deny existence in all its established forms, and rebuild anything at all in her own selfish form. But the divinity she hacked together as a shortcut into public reality is merely a byproduct in her pursuit of normality. She does not need any of it. Everyone in the show is constantly projecting their own will through Lain, trying to turn her into the persona device that benefits them most. It’s only at the very end, after all this torture, that someone finally thinks to sit down and talk to Lain herself about what she wants. The answer is, as you may expect, far more wholesome than the show’s sinister set designs would let on. To love and let love. That’s all she asks. The world is driven mad by the presence of the omnipotent Other, but if there is even one person who will smile at her, then god will smile right back. Lain is a shy girl whose ideal image is simply being at home in her bear onesie and chatting with her family over dinner. Whoever she is – whatever she is – and where on earth or beyond she actually came from, she just wants to be loved. Those rare moments where Lain has enough leave from all the forces wishing to antagonize her and simply embrace the world around her are some of the most cathartic story setpieces of all.

Certainly this was hugely influential and its dissociative presentation inspired many derivative psychosis works like Yume Nikki, GR Giant Robo, Doki Doki Literature Club or the like, but even still I once again emphasize that Serial Experiments Lain is written with such unfathomable narrative prowess that there is simply nothing else like it.

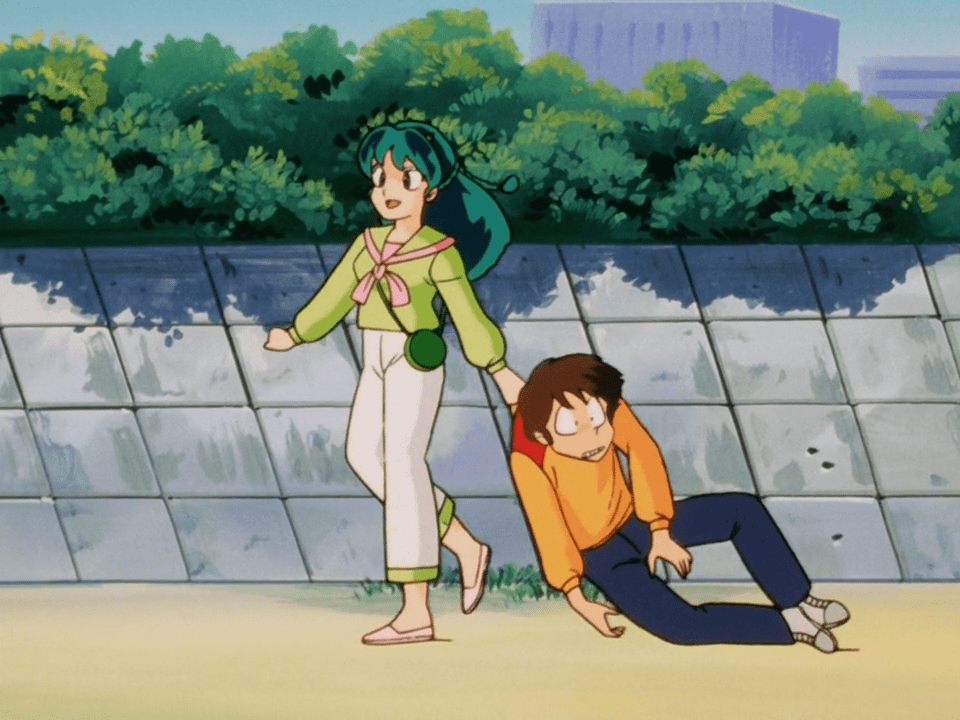

Urusei Yatsura is an outrageously high quality character comedy, save for certain non-PC relics that are far and few between but nevertheless unavoidable as a product of 1978. It’s a story about bad people being bad people to other bad people. Lum is a romantic tyrant who forces her way into Ataru’s home despite his many protests, while he is notorious for being the most unfaithful man in the entire universe. Shinobu is a shallow girl who only cares about riches and looks, Ran is a two-faced manipulator, Mendou is just as scummy as Ataru yet pretends to be his better, Cherry is totally self-centred and Megane is just kind of a creep. All of these obnoxious personalities are thrown into a 200 episode long mixing pot and before long it unsurprisingly ends up developing into a whole community of incredibly fun character chemistry and recurring jokes. Created in an era of experimentation the art and animation are often needlessly active, and it explores so many different genres and stylistic precepts through its additional catalogue of movies and OVAs. Once it gets into its swing it’s pure joy to watch.

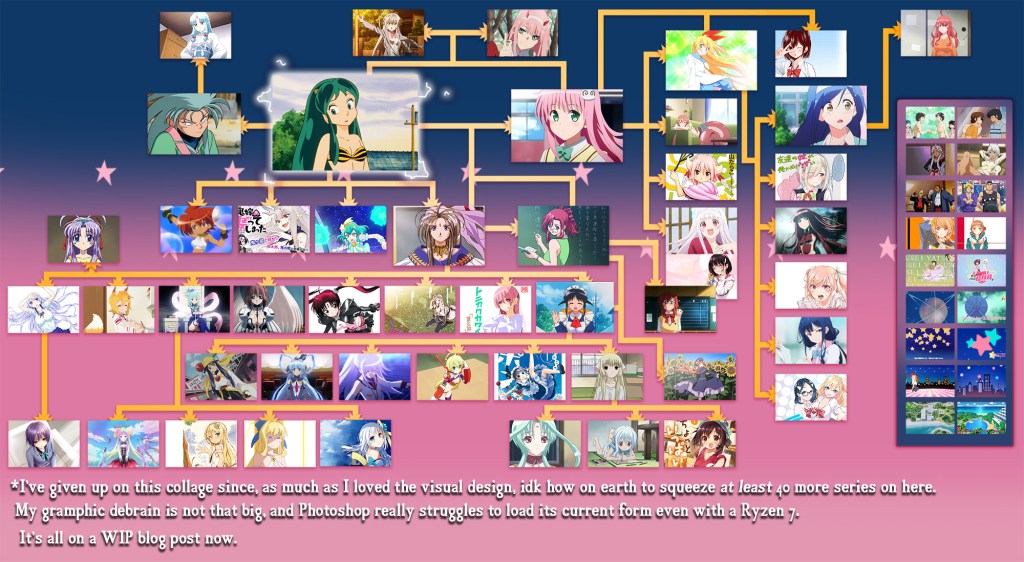

Beyond the show itself, I also get a lot of continued engagement with it in my ongoing “Lum lineage” categorization project. At last count I believe the number I had mentioned on my WIP script for the matter was around 90 series spread across animanga that I’ve observed with tangible references, homages and links traced back to specific events, character frameworks and story structures established by Urusei Yatsura. The way I see it, and where I see it, Urusei Yatsura is one of most central monuments in anime history. It’s just as integral as the elder gods of Astro Boy, Mazinger and Cutey Honey. It defined an entire sect of the medium and to this day, 40 years later, we’re still getting descendants of Lum. The demihuman-centric subgenre of cohabitation romcom it pioneered, which I’ve taken to calling the “Romantic Invader” for lack of a readily available term, is one of my lifelong favourites and combined with a noted interest in this realm of animedia evolution it ensures that Urusei Yatsura stays aggressively relevant in my mind.

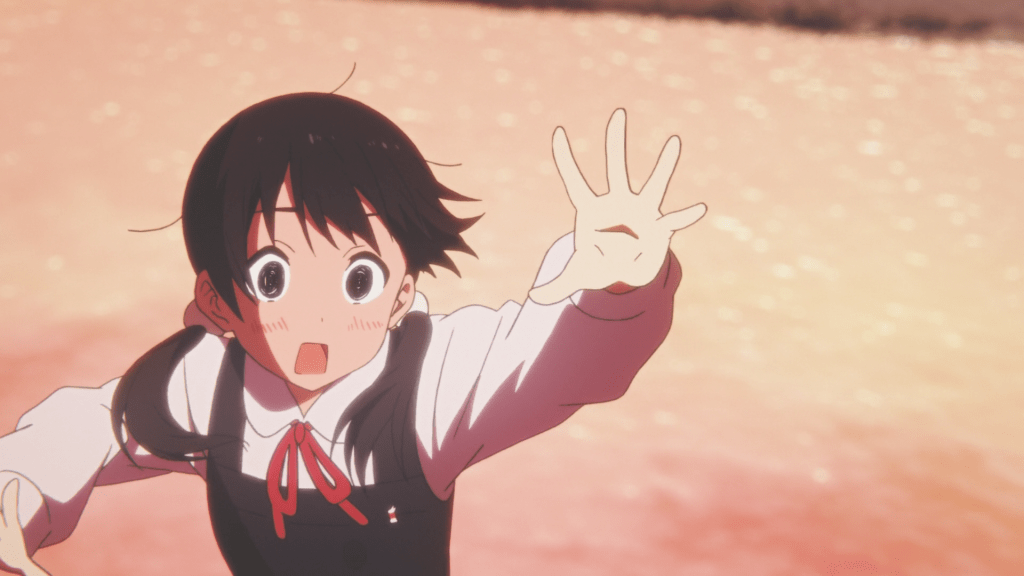

Love Live Sunshine. What could there possibly be to say for Love Live Sunshine after abstract peers such as these? Well, a lot actually. Perhaps moreso than any other anime I’ve highlighted in my time, if my feature-length discussion on the topic is any indication. “Confusing presentation, complex meaning and colourful personalities”, that was my broad motto I established in Concrete Revolutio’s paragraph. Is that really Love Live Sunshine? Absolutely it is.

Dismiss it with a mere glance of its genre at your own expense, for there is so much more to this than meets the eye. There is obviously much appeal worn right on its face. The music is catchy and traverses a surprisingly large amount of genres in jpop, kpop, metal, rock ballads, EDM, trap, synthwave, swing, broadway, eurobeat and everything in between. Aqours manage to make the token Christmas albums into something incredible of their own, for pete’s sake. Its immediate plot is compelling and the way in which it manages to create such personalized relationship dynamics in a cast of 9 main characters without feeling cramped is worthy of praise. On a personal level its shockingly well-realised rural setting tickles my own bush-loving heart too. There are so many frames in here that I swear I could step right into. Its locations speak such a familiar language to me.

But as I hinted at back in my paragraph for Gurren Lagann, the absolute biggest appeal of Love Live Sunshine, the part that makes it so magical an experience and for which it’s so readily overlooked, is again the writing more than anything. The unexpected ways it rocks the boat as an ambitious sociopolitical critique of the first series and all the character friction stemming from this idea of μ’s as the deified, depersonalised “light that can never be reached”, and its deceptively expansive imagery sets that turn an otherwise unassuming entry in an otherwise unassuming idol franchise into the Serial Experiments Lain of idol anime. From the enigmatic ethereal feathers, the warring rainbows, the water blue world and the miracle that sits just outside their grasp. Specific symbolic meanings trickle down even to the red colour of the protagonist’s eyes. Love Live Sunshine is a story about a group of rural schoolgirls trying to become famous and save their school. Yet at the same time it also uses its visual terminology to tell this understated tale of gods and monsters, those who eclipsed all to become eternity and those who are left crawling about in their wake. The star that guides and the star that shines. Every single thing that this narrative has to say is hidden beneath many different interlocking layers of symbolism, as Love Live Sunshine is for whatever reason just about the only genuine deconstruction that anime has ever offered to me. All the other entries in this franchise are outings immediately and entirely understood simply by reading the title of “Love Live School Idol Project”, but Sunshine is the dramatic exception to this rule. It’s an interpretive dance, or theatrical performance telling a tale about a monster’s dreams of place divine. Quite literally, mind you, given that the show opens and ends with actual curtain calls and frequently turns the spotlight upon its performers. What could there possibly be to say for Love Live Sunshine? That this is the anime that means the most to me. Plain and simple. From the rural setting, to the explosive characters, to the air of melancholy that pervades every element of the story’s energetic surface, it was as if me and the writers were on the same wavelength every step of the way and as a result this ends up feeling like something that was made specifically with my individual tastes in mind. This is the big one where I look around at others who rate it lowly, aren’t in the right audience for it or simply missed most of its true message, and the only thing I can think to myself is that I pity them for not seeing what I see in this.

Tekkaman Blade is situated in an incredibly well-realised setting that paves way for some of the most unique and compelling character drama I’ve seen in anime. The story is chock-full of striking twists and turns, and a plethora of different conspiracies which each transform the entire direction of the narrative with every new scrap of information.

This would be my number one if the production qualities were anywhere near decent. Although there is honestly quite some fun to be had in observing all the new and creative ways the show finds to totally forget its own visual design, it is nonetheless still a very major flaw. Which, speaking of the visuals, connect to Dangaioh, Dark Guardian Takegami and Detonator Orgun in one of those lineages I mentioned having a fondness for above. The story is top-notch, however. So much so that it’s all the way up here at #2 of my entire anime list despite its suffocating lack of consistency in the drawings. I always have praises I want to sing about Tekkaman Blade but no stage in which to do so since it’s realistically little more than a simple “Dang Tekkaman Blade is so good. That spoiler thing that happened was so powerful. Go watch Tekkaman Blade.” Even for those who would need some taste of the beautiful suffering that awaits them in order to truly become intrigued, or for those who are curious in the moment but will clearly never watch it, I cannot bring myself to peep even a word of it. I do not have it in me to spoil Tekkaman Blade. It’s thus a problematic little gem, and quite definitively the best anime that nobody ever watches.

At last arriving at the end and with Gurren Lagann already dealt with, my active favourite then is one Heartcatch Precure. As a meeting point between the deformative madness of Magical DoReMi and oppressively depressive atmosphere of Casshern Sins it can only be an artistic marvel, and the combat is every bit as expressive as one would expect when you consider that A) Precure as a franchise was conceptualised to be both Toei’s original spiritual successor to Dragon Ball Z and a counterpart series to Kamen Rider, and that B) Precure is enough of a cultural phenomenon that it’s pretty much always important enough to steal the budget from the studio’s other big hitters such as One Piece or Dragon Ball Super. So much so that the Dragon Ball Super: Broly film – an action piece totally in a production tier of its own – was the direct result of them uncharacteristically skimping on Hugtto Precure’s third cour. The artistic qualities of the franchise are incredible, and Heartcatch is the most experimental offering among its peers. But as has been said time and again in this rambling mess from someone who sincerely believes that grammar is courtesy and little else, it is the writing that truly shines through. The narrative defines the experience. It’s actually a rather dark tale told through the natural merit of the emotional weight each character has, not the sort of juvenile tricks that Madoka would become famous for in the following year.

In a twist of fate, it is often the stuff aimed at a younger audience that has the breathing room to properly engage with darker content, because there’s more of an expectation that it has to be done with respect in order to avoid inviting controversy. If we look at JRPGs, for example, you see things like NieR, Persona 5 or Tales of Berseria cited as the key ‘mature’ games of the modern scene. But NieR delves into tryhard grimdark territory and thus becomes difficult to take seriously, Persona 5 trips over itself so often on a thematic level that it feels like a self-sabotaging Disney film, and Berseria is one of the most juvenile things I’ve ever seen. Velvet is trying to imitate FFXIII’s Lightning in how she was actually a gentle girl forcing a harsh persona in order to get her job done, at least before she became the bland creator’s pet in the sequels, but Berseria does so without actually understanding the character nuance that made Lightning work so well. Her dialogue ends up sounding like 2005 Shadow the Hedgehog more than anything, and that’s about as far from what I would call mature as it can get. Whereas it’s actually something more innocent like Atelier Totori and Ayesha that are able to appropriately discuss the heavier topics. Totori’s story is all about slowly coming to terms with the death of her wandering mother, while in Ayesha there’s this bleak undercurrent of societal decline because the selfish alchemists of the past had almost entirely bled the land dry. They aren’t overly suffocating stories, but there is an undeniable sense of weariness that permeates throughout. It’s therefore no surprise that the Precure franchise isn’t any stranger to encoding rather adult plots between the lines. Hugtto’s main villain is the protagonist’s future husband, gone insane and come back to freeze time forever because she either died in childbirth or committed suicide in the timeline he came from. And Hana, for much of the show, hates herself enough that she can’t fully find it in herself to reject him. Healin’ Good (is what is quite likely the single darkest story arc in the series) hinges on a chapter of symbolic rape where one of the villains whom the protagonist had an odd amount of romantic tension with up to this point, forcibly implants her with a seed that is eventually birthed into a monster sharing both their physical traits. On the meta-narrative level, thus becoming a warning story about a sickly girl’s first foray into the wider world where she meets a man unlike any she’s ever known before, is taken advantage of by him, goes through abortion and ultimately struggles to muster the strength to scorn him the next time he comes crawling back for her body. For Heartcatch, it’s a tale of loss. Characters will be bullied by the narrative to expose entire lifetimes of trauma, and people do die.

Tsubomi’s refusal to look inside of herself, Dark Precure’s tragic pursuit of love, or the untouchable power that is Cure Moonlight – with the show being planned so well that once she does finally rejoin the lineup she’s even more overpowered than her legacy had let on, yet implemented in a way that somehow doesn’t damage the stakes in any capacity. Like, once Moonlight shows up around 3/4s of the way into the show, the Heartcatch have already won right then and there. Of course being the heroes that’s not necessarily something that was ever in question, but it’s more that the level of power Moonlight exhibits means that they’re frankly never going to lose a battle again, because nothing can even touch her. Unlike most other entries the Precure are not called to action by any nondescript god or the desperate cries for help from a neighbouring fairy, but specifically to inherit her will after she sacrificed her ability to transform, and even three of them are still barely enough to make up for it. She requires the entire collection of Heart Seeds to fuel her transformation rather than a single tact, and when she does finally decide to fight once more the entirety of nature sings for her in a way that it never has before. The villains quake at her name, knowing that she’s a ticking time bomb where their window of opportunity will be over the second she steps back onto the battlefield. They put so much care into the background narratives to build up how fearsome of a force Moonlight is. The long-term scale of which then itself is used to establish a palpable sense of urgency and imminent danger when the final villain appears out of thin air and turns the world into a desert, which they had spent the entire series fighting to prevent, in literal seconds. Every aspect of Heartcatch Precure is designed to interact in such potent ways as these.

The story makes full use of its longer pacing with the large amount of story threads running beneath. In every successive battle you can feel the frustration between the two sides pooling, knowing that at some point it has to froth over. It manages to find ways to one-up itself every episode, and then when you finally reach the point that you believe you’ve seen absolutely everything it has to offer and are already preempting the mental review in your head, a giant man punches the planet. The scale of the show steadily widens in order to narrow into individual layers of the protagonist. It’s structured in such a way where you can tangibly feel every single episodic resolution feeding into Tsubomi’s growth, from the weakest Precure in history to someone who can carry the weight of the entire world. Heartcatch displays a maturity well beyond its years, and together with its overwhelming aesthetic prowess it all clicks together like you wouldn’t believe. This is as close to anime perfection as you can get.

Leave a comment