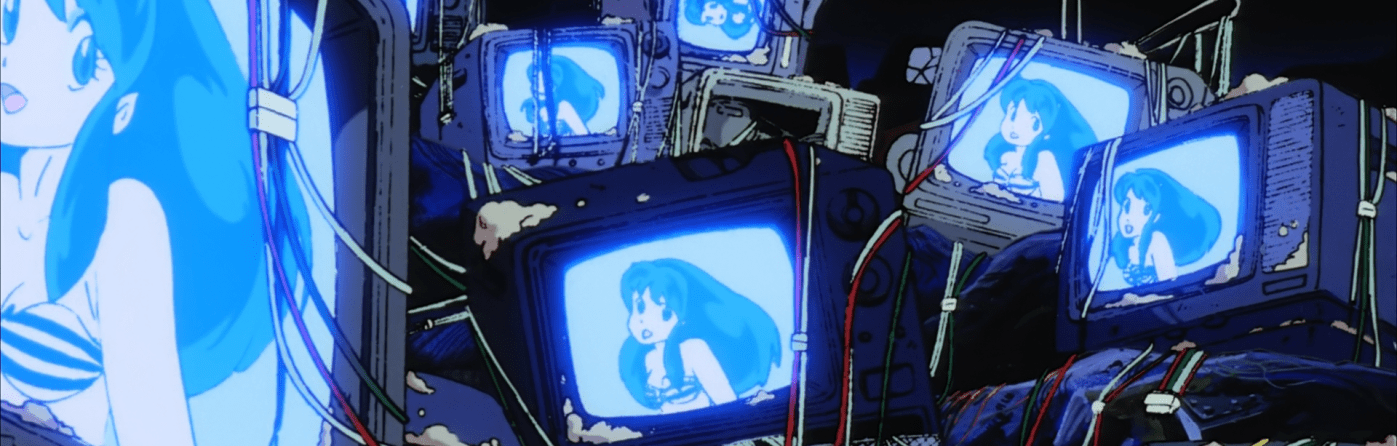

While Urusei Yatsura is a series primarily devoted to fulfilling its role as the animanga scene’s pioneer cohabitation romcom, the 1986 movie Lum the Forever stands out as a mysterious departure from the norm. It’s the franchise’s premier arthouse piece, where its usual insanity temporarily spills over into a full-fledged case of disassociation, and the setting’s natural instability paves way for a story of reality crumbling around its characters. Tomobiki’s corporeal definition is called into question, and the physical world becomes a vague, hazy existence. In all honesty, a large part of Lum the Forever feels like it’s ambiguous purely for the sake of being ambiguous. Compared to other confusing things it almost feels like it’s not that it has something to say, but that it wants you to make it say something. Usually when I write any kind of reflective piece it’s to do with established feelings or ideas I’ve been sitting on since watching the show, and so rewatching Lum the Forever with the primary intention to grasp at something to pull out of it illustrates the difference in style, since that’s precisely backwards of the usual method. Ultimately the way I ended up understanding Lum the Forever is that it’s somewhat of a sentient film. In order to signpost this it begins and ends with shots of a television screen, and the entire story is framed by Megane’s film project and a video-centric aesthetic. Lum the Forever is a film about film. Or about the audience that silently gaze in from the outside, rather. It comes as no surprise that when a story tells a tale centred around film production, symbolic systems and consciousness, that it is then waiting to be read from the perspective of such scholars who deal in film production, symbolic systems and consciousness.

The story opens on our main cast during the filming period of one of Megane’s frequent video projects. For the big climax of their independent production Mendou has agreed to let them chop down an ancient tree, dubbed Tarouzaka, that his family has been protecting for centuries, believing that it’ll make for a beautiful setpiece with which to close out the scene. They had already decided it’d make more sense to use it for this and transplant parts of it later to regrow, since the tree had been rotting on the inside for a while now and likely wouldn’t survive winter. But when they strike it with the axe the tree begins writhing with pain and frothing at the cut. With its death throes ringing out through the night sky, the tree collapses to the ground, leaving behind naught but its strangely grotesque ribcage, and a crowd of very confused onlookers. It’s from this point that Lum the Forever truly begins. As the characters later figure out, the dreamlike events unfolding all trace back to this opening event where they cut down the sacred tree. Only after this happens does reality begin to be torn asunder. In this way we can force Tarouzaka to be representative of the metaphysical author figure, that transient existence which defines the world. ‘The author is dead, and we have killed him’, as it goes. The script laid to rest, the setting discarded to the void, and the world in which these characters inhabit transformed into an ill-defined vacuum that shifts with every tangential thought. Without the author to anchor them down, anything and everything becomes a malleable mess of manufactured memories.

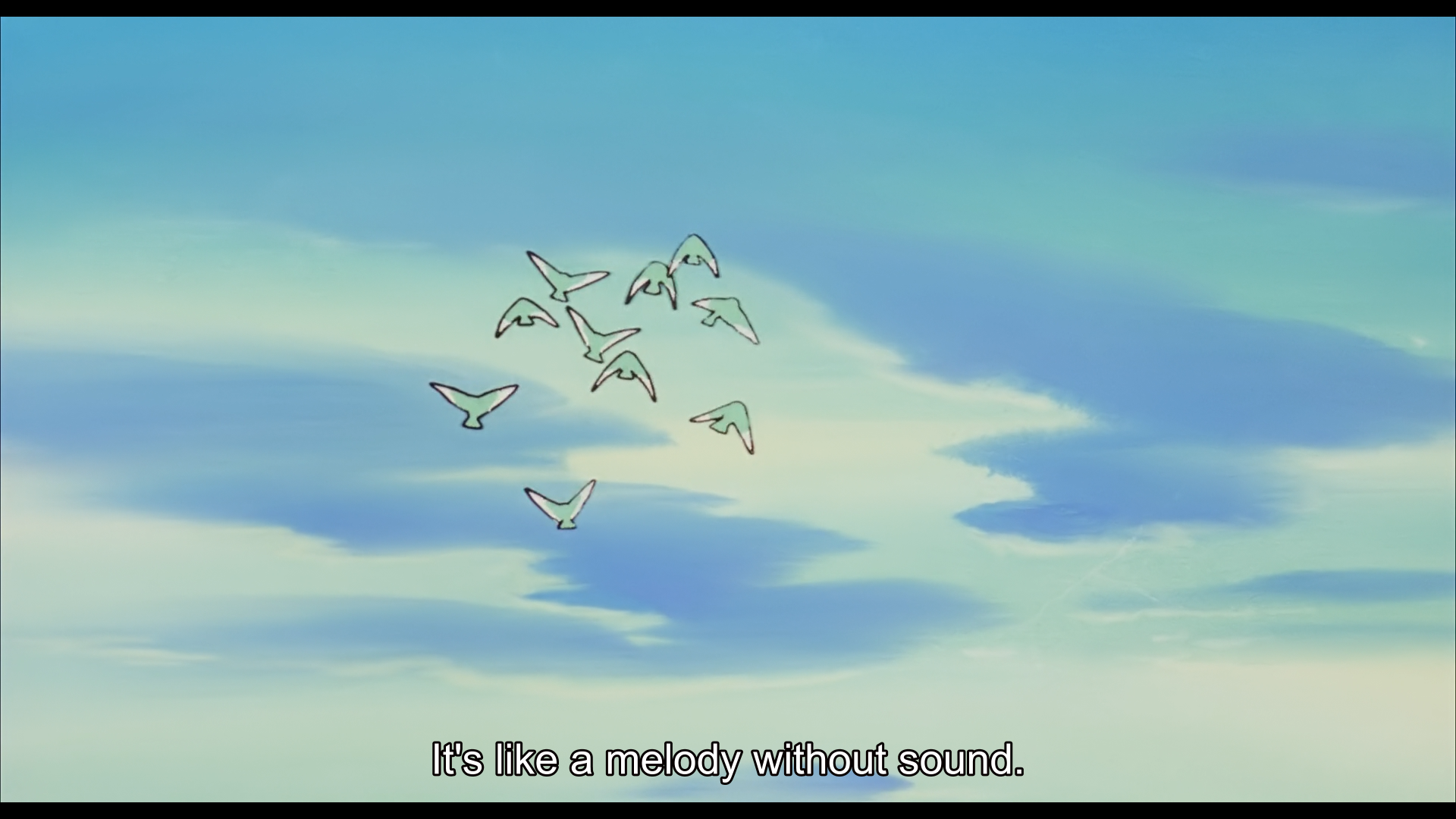

As a result of this rampant destabilisation, some hidden force begins to stir. A giant consciousness hanging in the air around Tomobiki. The ether quakes as the ever-present being is freed from that which once placated it, and the illustrious spectator opens its eye. The thematic significance of a spectator within the backdrop of the film pertains to a specific application of Jacque Lacan’s Psychic Triad, a consciousness model he’d been toying with since the 30s, but first properly developed in the area of 1950. According to his theory the recognition of self comes in three different modes. We begin life in what he refers to as the all-important Imaginary Register. This is the pre-language period when an infant does not yet recognise itself as having individual form. It exists in a kind of primordial unconscious, simply gazing out at the world and not yet realising that it occupies a physical avatar separate from others (Lacan 1997, pp.2-5). Within the film, this concept is most centrally represented through the little birds that repeatedly flock to Lum. Unable to make use of human symbols, the animals shouldn’t be able to communicate with any of the characters. Yet they do so with ease. The “melody with no sound” that the girls refer to can then be taken as allegorical to the Imaginary. It communicates through a formless intuition rather than language, and becomes increasingly harder to grasp as they grow older. Returning to Lacan, once the fledgling existence observes itself on any mirror-like surface it becomes painfully aware of its own fragmented self, and the Imaginary stage is lost forever. Life continues, and the child grows. The family and society around it all begin to teach it language, and it slowly comes to accept its own position in the world. The specular I becomes the social I (Lacan 2006, p.79). Perhaps the rate of separation does differ for Lum, as glimpsed in the dialogue contrasting Mendou’s declaration about her being a foreign, alien object with Ataru’s early line about always wanting to remain human, but regardless her connection to the Imaginary steadily declines with age. Her and Ran both remark that “the sounds” aren’t as clear anymore. They are already 17, after all. This sentiment forms the basis of the next phase, the Symbolic Register, in which the symbolic systems of language and encoded messages tell us how to relate to ourselves, to others, and to the world around us, and thus incite the formation of ego (Laplanche & Pontalis 2018). The third option, the Real register, is not particularly relevant to the discussion at hand, and so shall be skipped.

Now, aside from keeping the basic definitions in mind, the key point to take away from this is that ordinarily there is not supposed to be any way to return to the Imaginary, for once one is dyed in the dialectic of the Other they are lost to it forever. It’s a permanent paradigm shift that fundamentally rewrites the way we understand physical and social space. The ambiguous nature of the Imaginary means that the second you perceive it, it ceases to exist. But actually, cinema has long been suggested to be such a method for channelling it, an idea most notably put forward by French film theorist Christian Metz. The Imaginary is shattered by the Mirror Stage, wherein the infant first glimpses its own form and subsequently loses its capacity to be a formless observer. However, is that not the very definition of cinema? The lights dim to help you forget the distraction of your own body in your peripheral vision, and the movie allows you to silently peer into its world. The cinema screen acts as a mirror which doesn’t reflect, and thus invokes the Imaginary (Metz 1982, p.45). You go to the movies, and for the next two hours are permitted to forget yourself and all your surrounding circumstances as you slowly melt into the story.

Over the course of the plot, Lum is sought after by the fog now inhabiting the city, and extended a rare invitation into this emptiness. Her ego, that which serves as one’s connection to the Symbolic, or to the public sphere, is slowly shut off as she loses defining parts of her outside identity, such as her flight and electricity. At first she’s just subtly vanishing from people’s line of sight, but this rapidly escalates and before long she’s disappearing from everyone’s memories. Consequently, so too does she gain an increased perception of “the sounds” as her consciousness swells to cover the entire town. The spectator beckons her over, and she ultimately ends up accepting its offer. Descending to the bottom of the lake and taking up the fetal position as she sets her sense of self to sleep, Lum is spirited away by the silver screen – temporarily traversing back into the Imaginary.

With Lum now firmly seated in the audience, the narrative structure (or presentation) begins to mimic, well, film. Lum sits just outside everyone’s field of view, watching their various dreams unfold like a marathon of movies while she tries to ascertain the identity of that which called her so. After much wandering, Lum at last confronts the Imaginary spectator who had dragged her this far. It manifests as a giant infant just barely capable of speech, as if doing its best to reach out while still keeping the Symbolic held at bay. Conversing with it finally draws out the true identity of this invisible adversary. The mysterious force that had been moving behind the scenes was in fact the will of the town itself roused into action. Stepping back into the surface of the narrative again, the Tarouzaka cherry blossom was something of an author yes, but this pertains to its position as a guardian deity, which is due to it housing the remains of the Onihime from the legend that Megane’s video project was based on. If we thus read it to be something of a father figure while in this guise, then it also contextualises some more of the imagery in this scene. On the advent of Tarouzaka’s fall, this formless child no longer had anyone to direct it, and so it extended an invisible hand into the world above. Suspended in the Imaginary as an amalgamation of collective memories and unconscious inclinations, something that conceptually persists but has yet to truly be born. In the wake of its original author’s death, it sent out a desperate cry like electric signals rushing through power lines, hoping that someone would pick it up. During the town hall where the Tomobiki residents begin discussing emergency measures they theorise that the reason for Lum being elected its representative must be due to her own strength of will far surpassing anyone else’s. As previously noted Lum, Ran and the rest of the weird space cohort can be seen as still having a modicum of connection to the Imaginary, perhaps informed by their sense of harmony operating on an intergalactic scale, far beyond anything the landlocked human mind had ever experienced. The message ultimately resonates with Lum, for she is noted to have the loudest consciousness, one absolutely bursting with its sheer affinity for life. And so she is summoned thus.

If her aggressive expression is any indication, Lum had originally accepted its invitation into the abyss in order to reprimand it for its interference. Her powers had been stripped from her, and the place she called home thrown into question. Of course she was mad. But by engaging with it she comes to understand that the fragile spectator simply wished to find stability in the wake of Tarouzaka’s end, and so makes peace with it. The entity speaks only of the past, as if it lacks a future. Indeed this is due to it taking refuge in the Imaginary, performing a psychoanalytical balancing act while attempting to avoid truly falling into ego. This is an understandable response for a being shown in such a form as this, since according to Lacan’s writings about the Mirror Stage, it certainly isn’t anything pleasant. He describes it as an experience which inspires a sense of “primordial jealousy” (Lacan 2006, p.79). The suggested Imaginary-Symbolic transition is one of losing completeness to become fragmented, after all. It pursued her in order to choose a new author, not to step into the conscious order and adopt the mantle itself. Therefore after playing with Lum for a bit and probing her subconscious mind through various hallucinations, it gains a proper appreciation for just how much affection Lum had to offer for the town, and so decides to entrust the future to her. Satisfied, the cryptic overseer accepts Lum’s interpretation of the fantastical film set that is Tomobiki town, and the memory of the Imaginary returns to slumber. Elsewhere, the self-aware actors of Lum the Forever forcibly instigate the narrative’s final battle as a means to make Lum leave her seat. The spectator’s viewing session has drawn to a close. Lum is ushered out of the metaphorical theatre and back into the everyday Symbolic realm. No longer deprived of an author as a result of this intervention, Tomobiki returns to the way it ought to be. In a spot unseen by anyone else, the television screen fades back out, and the movie ends – both for us, and for those in-universe observers who had been watching. The town’s past memories are once again buried alongside the spectator as it relaxes its strained sense of language and returns to Imaginary nonexistence, and the pen with which to write the future falls upon the outstretched hand of one hopelessly romantic alien girl.

That’s one such reading of sections of the imagery, at least. Since Lum the Forever is, at the end of the day, a work that defies any one codified explanation. With its dense symbolism and deliberately obfuscated meaning, there are as many valid readings as there are viewers. Something which I have accordingly ascribed to the death of the author – both in concept and in narrative, evidently.

References

Lacan, J 1997, ‘The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience’, Écrits: A Selection, trans. A Sheridan, Tavistock, London

Lacan, J 2006, ‘The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience’, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. B Fink, W. W. Norton & Co, New York

Laplanche , J & Pontalis, JB 2018, The Language of Psychoanalysis, Routledge, <https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=RptYDwAAQBAJ>

Metz, C 1982, ‘THE ALL-PERCEIVING SUBJECT’, THE IMAGINARY SIGNIFIER: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, trans. C Britton, A Williams, B Brewster & A Guztti, Indiana University Press, Indianopolis

Urusei Yatsura Movie 4: Lum the Forever 1986, film, Kitty Films, Japan