Released in 1997 by studio Gainax, the anime film End of Evangelion served as the finale to the story established in the preceding Neon Genesis Evangelion TV series. It has since become an incredibly revered and aggressively relevant film for its intense, abstract mysticism and willingness to depict scenes of such heavy psychological and physical turmoil upon its characters. The protagonist Ikari Shinji is an extremely fragmented and mentally unstable individual. Resulting from the premature death of his mother, he is unable to truly understand or accept human affection, walling off his heart in order to try and protect himself from being hurt by others. But by traversing his memories and traumas through Rei’s guidance in the reality-warping event known as Third Impact, Shinji is eventually able to make peace with his painful past and step out into the world a refreshed human being.

In this scene Shinji and the rest of humanity are swept up in Third Impact, wherein their souls are forcibly liberated and joined together as one superorganism in a state of existence dubbed Instrumentality. Evangelion is a franchise incredibly heavy on its incorporation of psychological concepts, particularly those related to the topic of human interaction. It doesn’t take much effort to read this scene as a symbolic representation of the psychiatric process, with Shinji as the subject having his psyche and neuroses explored, and Rei as the psychoanalyst who is guiding his introspection. During the beginning stages Rei has a back and forth dialogue with Shinji as she attempts to make him take back his statements that all of humanity should just die – an act which clearly depicts the psychoanalytical process. Acting as psychiatrist, she is engaging with his negativity, probing him to try and make him reach reconciliation with his own two hands.

The representation of Misato’s apartment that the sequence begins in is to be interpreted as the turmoil occurring within Shinji’s subconscious rather than as a physical memory. In the ethereal room, Asuka rejects Shinji’s pleas for help and he begins screaming “Don’t leave me alone! Don’t abandon me! Please don’t kill me!” This line essentially encompasses Shinji’s entire character. Shinji is someone that places his self-worth far too heavily in the acceptance of others, and thus is unable to truly love himself or those around him, and it is for this reason that Rei stages this supernatural intervention.

With Asuka’s stern refusal to save him Shinji abruptly lurches forwards to begin choking her, and as the music rolls in Third Impact begins. From a technical standpoint, the usage of the English song ‘Komm, Susser Tod’ (a German title translating to ‘Come, Father Death’) throughout the scene illustrates the instability of Shinji’s subconscious, as it creates a sense of discord when juxtaposed against the Japanese dialogue. It quickly flashes through the title cards of all the episodes from the TV series, and then moves on to display animation keyframes from the television series to present the intertextual link that this is finally going to be the end to the story and the character progression established in the original show.

Once Third Impact (representing Shinji’s psychiatric deconstruction) is initiated, childlike drawings depicting scenarios of gruesome death and mutilation flash up on the screen. As a child Shinji was exposed to death at a very young age, which instilled a deep-seated fear of dying within him. During this era of his life, his mother and father were working with SEELE on the Evangelion Project. Trials were proceeding around the working theory that each Evangelion required a soul in order to function, thus during the preliminary stages his mother Yui volunteered to put her own soul into Unit 01. The experiment was more or less considered successful, but the vanished Yui declared dead after her absorption into the bioframe. On that day immediately following her disappearance, young Shinji stood alone inside the Gehirn control room as sirens blared loudly and adults panicked frantically around him, an experience so traumatic to a young child that it became deeply carved into his subconscious. After the loss of Yui, his father Gendo was quick to throw himself into his work and pawn Shinji off to relatives to take care of. It is made clear how much this abandonment has affected Shinji when the shot of little Shinji alone on the train platform flashes up, and he asks Rei “is it alright for me to be here?” When queried Rei remains silent, and in response Shinji lets out the most blood-curdling scream I’ve ever heard in cinema.

Nevertheless, as a psychiatric move this silence was necessary. The biggest neurosis holding Shinji down was his constant reliance on others to affirm his existence – if others didn’t need him then why was he alive? By remaining silent, Rei rejects his entire reason for existing. Her intention is that by completely tearing down Shinji’s unhealthy lifestyle, it will later allow him to start afresh and finally find his own reason to live. As the film’s tagline says, “the fate of destruction is also the joy of rebirth” – Shinji must be broken apart and rebuilt anew. This is also represented visually, as after the ‘silence’ shot fades out, we see keyframes of Shinji being scratched up beyond recognition, symbolising how his character was being sliced apart.

![The.End.Of.Evangelion.720p.x264.Trial_Audio-RobotCanti.mp4_snapshot_01.06.28_[2019.05.28_18.39.03]](https://skapbadoa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/the.end_.of_.evangelion.720p.x264.trial_audio-robotcanti.mp4_snapshot_01.06.28_2019.05.28_18.39.03.png?w=736)

This insatiable need for the approval of others can be tied to the Freudian concept of castration anxiety, an idea that “what brings about the destruction of the child’s phallic genital organization is this threat of castration.” (Freud & Strachey 1961). On a subconscious level Shinji held his father in contempt as the one who took his mother away from him. Like castration anxiety where the male child fears the father will take his phallus just as he took his mother’s, Shinji has an innate fear that if he stops being useful his father will kill him just as he killed his mother (even if this fear is not entirely logical due to the nature of his mother’s disappearance).

Deep down, the loss of his mother and rejection of his father has made Shinji existentially frightened at the notion of engaging with anyone in earnest. One of the most prominent conflicts each character in the franchise struggles with is the Hedgehog’s Dilemma, a metaphor about human interaction that Freud appropriated for psychological purposes from a philosopher named Schopenhauer. It is a parable that speaks of hedgehogs “huddled together […] to prevent themselves from being frozen” in winter, only to “soon [feel] the effects of their quills on one another, which made them again move apart” (Schopenhauer & Payne 1974). Putting this into simpler terms, the Hedgehog’s Dilemma is about finding the appropriate emotional distance where one can still benefit from interpersonal bonds while avoiding the pain associated with getting too invested in one another. In the case of Shinji, it can be seen in the way he attempts to maintain a safe distance from others, and avoids ever making any major decisions for himself. During the TV series it is revealed that Shinji can play the Cello, and when Asuka queries him on why still plays even though he doesn’t like it he responds “because nobody ever told me to stop”. Similarly, after temporarily running away from NERV in Neon Genesis Evangelion, Misato tells him to leave if he doesn’t want to be there, and Shinji (being unable to make his own decisions) can only remain silent. However after achieving solace within himself, Shinji finally stands up for himself and reaches his own conclusion to regain his humanity.

In addition to this abandonment complex, as one starved of his mother’s love Shinji exhibits hidden yet undeniable Oedipal tendencies, a Freudian concept where “boys concentrate their sexual wishes upon their mother and develop hostile impulses against their father as being a rival” (Freud & Strachey 1935). Near the end, there is a shot of Shinji’s face as he is lying down looking up at women riding on top of him, first at Misato, then at Rei, in shot composition portraying a sexual intimacy.

This is clearly drawing attention to Shinji’s Oedipal hangups. Misato can be seen as somewhat of a mother figure to Shinji due to the way she invites him into her home with the promise to take care of him, while Rei (unbeknownst to Shinji) is a clone of Yui that Gendo created after her death. Furthermore, Yui’s soul is sealed within the core control unit of Unit 01, and therefore the very act of Shinji getting inside the entry plug and piloting her is inherently Oedipal. According to Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, the child’s Oedipus complex subsides around the end of the Phallic phase (3-6 years old), at the time when castration anxiety and the subsequent formation of the superego cause “the child’s ego [to] turn away from the Oedipus complex” (Freud & Strachey 1961). The problem then, is that when his mother was taken from him Shinji was only 4 years old, and thus had not completed his phallic phase of psychosexual development. The interruption of the phase via the death of his mother meant that his complex was never resolved, and for this reason its influence can be seen underpinning his character throughout the story. But in the finale of the movie that occurs following this sequence, Shinji rejects Rei’s Instrumentality and returns to Earth alongside Asuka who does the same. By rejecting the Oedipal (Rei) for someone outside his family, it shows that the psychiatric therapy (Third Impact) has helped him to overcome his developmental problems.

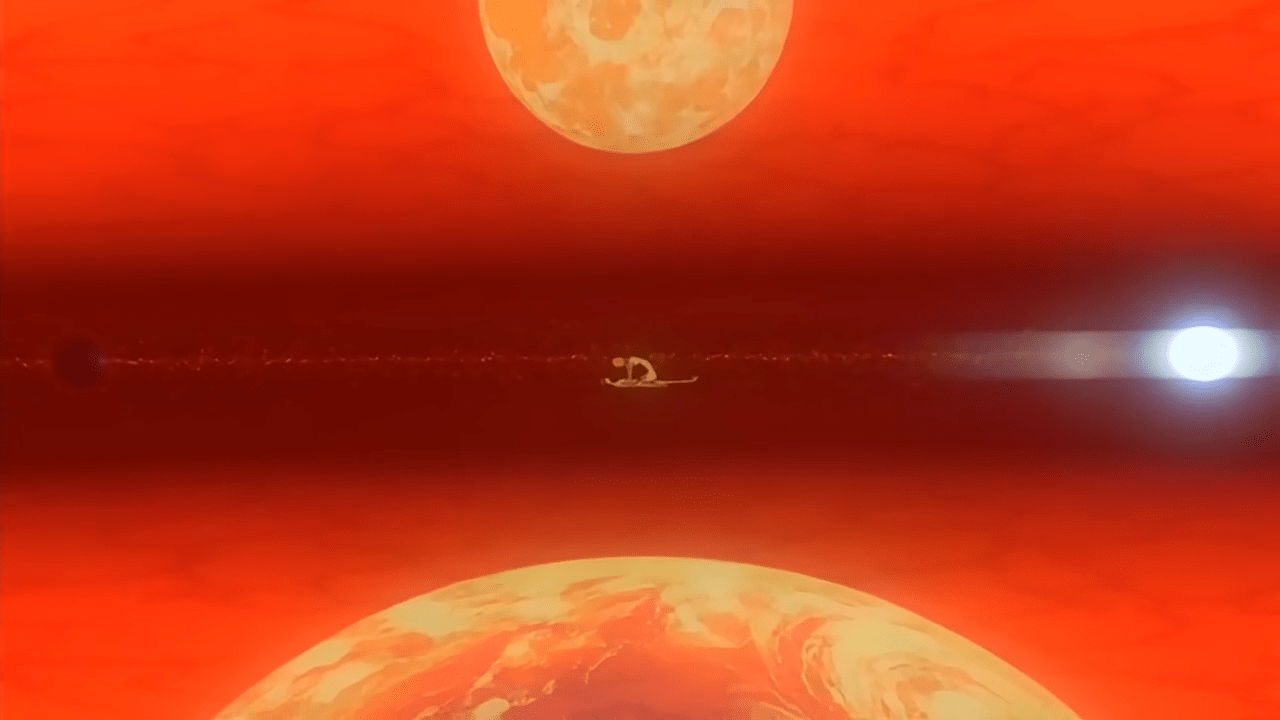

Stepping away from the scene itself and delving into the lore then, it can be observed just how deeply ingrained the works of psychoanalytic theorists are in the world and story of Evangelion. SEELE’s Human Instrumentality Project is a central thread running all throughout Neon Genesis Evangelion, and therefore the triggering of Third Impact as the prelude to Instrumentality in End of Evangelion is essentially the culmination of the entire series. Instrumentality is a by-product of Third Impact that entails the collapse of all mankind’s AT Fields, losing the ability to maintain their separate forms and joining together as one. The AT Field is a core concept in Evangelion described as the border around one’s soul. Losing their bodies due to the worldwide Anti-AT Field that Lilith had spread out, humanity reverts into LCL (an orange liquid equivalent to the primordial soup of life) and merges together as a single existence – the sea of LCL. During this, Rei remarks that:

![The.End.Of.Evangelion.720p.x264.Trial_Audio-RobotCanti.mkv_snapshot_01.16.53_[2017.11.29_20.27.55]](https://skapbadoa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/the-end-of-evangelion-720p-x264-trial_audio-robotcanti-mkv_snapshot_01-16-53_2017-11-29_20-27-55.png?w=736)

This idea of ‘not knowing where one person ends and the other begins’ is a reflection of Lacan’s Imaginary register. The Imaginary register is defined by Lacan as the time “in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other” (Lacan & Sheridan 1977). Decoding that into something easier to understand, it is the pre-language period when an infant is not yet aware of its fragmented self as separate from other humans. What is next most important then, is Lacan’s subsequent idea of the Mirror Stage. In the Lacanian Mirror Stage “the structure of reflected identity that gives rise to the ego […] is an object for the subject, an other for the subject” (Muller 1985), meaning that the establishment of identity is entirely due to external influences, being informed by the Other (the Other simply referring to anything that it is not I); the infant witnesses itself in the mirror (“the structure of reflected identity”) but despite observing itself it doesn’t innately recognise its own individual form, and thus this is the first time it recognises itself as a distinct corporeal being (“an other for the subject”), which leads to the development of sapient self-recognition (“that gives rise to the ego”). In mentioning this, it’s tangential but I’ll draw attention to the fact that End of Evangelion’s soundtrack contains a song called ‘Interference of Others’ – a title which reflects Lacan’s comments about the outside formation of self. In following with Lacanian developments, Shinji rejects Instrumentality (the Imaginary stage) by recognising his reflection within the ocean of LCL and deciding that he wants to return to being himself. By finding his individual self within the reflective nature of the LCL, he undergoes the separation from the collective human unconscious that the Mirror Stage entails. Or as the title for the final episode of the TV series so eloquently puts it, Shinji becomes “the beast that shouted ‘I’ at the heart of the world.”

With this, Shinji and Asuka return to the surface of the planet, and the story comes to a close. Suspended at the border between the Imaginary and the Symbolic, Shinji finally achieves relief from the mental dilemma that had plagued him since childhood, now taking refuge in his fragmented self. Through this, End of Evangelion portrays the psychotherapeutic process as an irreplaceable complementary component of the human condition. With Rei’s guidance Shinji is able to overcome his neuroses and make peace with his deepest repressions, departing from the safety of the Imaginary stage (shown as Instrumentality) in order to try his best at living as an individual again. Through the psychiatric deconstruction that Rei helps to work him through he finally enters into a period of true equilibrium within his mind and heart, and emerges a healthier soul. By weakly choking Asuka one final time he confirms that she and him are indeed different people after all, and finally he lets loose his tears.

References

Freud, S & Strachey, J 1961, ‘The Dissolution of the Oedipus Complex’, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Hogarth Press, London, vol. 19, pp. 175-176, retrieved 29 September 2017 < PEP web link>

Freud, S & Strachey, J 1935, Sigmund Freud ; an autobiographical study, Hogarth Press, London, p. 10, retrieved 30 September 2017 <http://www.mhweb.org/mpc_course/freud.pdf>

Lacan, J & Sheridan, A 1977, ‘The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience’, Écrits: A Selection, Tavistock, London, pp. 2-5

Muller, J 1985, ‘Lacan’s mirror stage’, Psychoanalytic Inquiry, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 238

Schopenhauer, A & Payne, EFJ 1974, ‘Similes, Parables, and Fables’, Parerga und Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays, vol. 2, p.652

The End of Evangelion 1997, film, Gainax Co., Tokyo

Leave a comment